«

Contents

|

|

Digital Art History - A Subject in Transition: Opportunities and Problems |

Stephen Clancy

Ithaca College, New YorkThe Cathedral as a Virtual Encyclopaedia: Reconstructing the 'Texts' of Chartres Cathedral

Keywords: Charles Cathedral, digital visualisation, QuickTime VR panorama

Imagine that you are an architectural historian five hundred years hence, who is interested in the meaning that the British Academy building held for those who used its spaces and viewed its surfaces at the turn of the 21st century. You would certainly be interested in the attitudes and images these audiences brought to the experience – the thoughts, visual memories, and beliefs that acted as the lenses through which the physical environment was experienced. You would also realize that the building acted as an architectural umbrella for experiences that varied over time and space, and between different users and different occasions. At the very least, you would have to concede that the building was not a static entity: its impact clearly varied with the experiences and attitudes of the individuals who moved through its spaces.

A static, fixed interpretation is precisely the sort of exercise that most students of medieval architecture are offered today. This is especially problematic with the Gothic cathedral, which is the focus of this project. Traditional methods of presentation and study – for example, the art-historical slide lecture – can only hope to summarize abstractly the dynamism of the Gothic cathedral. As Professor Robert Calkins of Cornell University has so aptly put it, the Gothic cathedral "is an encyclopedia in stone and glass, the summa of medieval architectural form.1 " It functioned as a multifaceted cultural 'text' that was both 'written' and 'read' by its varied users. The sculpture on its doorways, for example, embodied rich and seemingly contradictory concepts of judgment, compassion, chivalry and power. The figure of St. Theodore from the North transept portals was probably understood differently by those from different social classes, and one's reception of the sculpture might well have varied depending upon the nature of one's past experiences with the French knightly class. Even the spaces themselves encoded ideas about social hierarchy, with different classes of society being permitted different levels of access and freedom in the cathedral's interior spaces. While tourist groups wander freely through it now, a medieval worker in the vineyards was forbidden to set foot in the choir ambulatory of Chartres Cathedral during services,2 and would have approached and experienced the building and its imagery in a vastly different fashion from that of the Dean of the cathedral's chapter.

Today we, in our turn, attempt to 'read' this architectural 'encyclopaedia' in order to understand the religious beliefs, cultural values, and secular practices encoded within it. But our own cultural attitudes and educational practices get in the way. We view the cathedral and its environment through modern lenses of tourism, commerce, or "fine art," instead of reading their significance through the lenses of medieval cultural attitudes: in essence, we experience the cathedral as 21st-century visitors to one of the "great sights of the past," instead of as 13th-century participants in one of the dominant, contemporary social institutions. In addition, the slides and photographs we use to explain the cathedral treat the building merely as a series of static, two-dimensional visual compositions, devoid of spatial continuity, and divorced from the urban and social contexts that gave it meaning. Indeed, the static isolation of the slide has given rise to the side-by-side "stylistic comparison" approach,3 which treats the history of medieval architecture as an evolution in style, as if the buildings were oil paintings by Monet. The early Gothic façade of Chartres Cathedral, for example, is said to have 'evolved' into the High Gothic façade of Amiens, which, in turn, 'evolved' into the proto-Flamboyant façade of Reims.

Our modern, static images are also unable to evoke the original appearances of these walls and spaces of the cathedral and its urban environment, in large part because the cathedral's structure, imagery, furnishings, and surroundings have changed or vanished over time. The loss of the cathedral's medieval urban environment is particularly significant. To experience a cathedral after parking in an underground garage, traipsing through a Monoprix, and sipping an espresso at a café is quite a different thing from viewing it at the end of a weeks-long pilgrimage on foot, after travelling through fortified gatehouses, up shadowed streets filled with merchants' stalls, and past money-changers crowding the transept portals. The "Virtually Reconstructed Chartres Cathedral" project was conceived as a way of using recent and rapid advancements in digital technologies and software as tools for beginning to bridge this gulf between the 21st and 13th centuries. It was also conceived as a way to substitute a dynamic, interactive, and spatially continuous experience of the cathedral for the static and passive experience that most classrooms provide. Chartres Cathedral serves as the vehicle for this project because it brings us closer to the 13th century than most other cathedrals. Much of its original stained glass, sculpture, and structure survive relatively intact; it still houses a number of its medieval liturgical objects and relics; the 13th-century street plan around the cathedral largely survives; and even a few late-medieval houses still stand along the access routes to the cathedral. The project was inspired, in part, by the Amiens Cathedral project, created by Stephen Murray and a team of multimedia designers at Columbia University. This web site,4 funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities, demonstrated the value of using digital technologies to make accessible a variety of contextual materials about a cathedral. It also pioneered the use of panoramas to recreate virtually a sense of the spaces within a cathedral.

Building upon these efforts, the Chartres Cathedral project proposes to use digital technologies to accomplish four goals: (1) to simulate digitally the 21st-century architectural spaces in and around the cathedral; (2) to provide a means of interacting with these 21st-century spaces, and the images and objects within them; and (3) to simulate digitally the 13th-century architectural spaces; and (4) to create a sense of how they were experienced by their varied audiences in the later Middle Ages. Obviously a project such as this requires a considerable amount of human, institutional, and monetary support, and here I have been fortunate. Ithaca College supported the project with course release time, and also funded two trips to Chartres, so that I could shoot the images that form the basis for the panoramas. In addition, I have received support from two broader institutional grants, the first from the Keck Foundation, and the current grant from the Hewlett Foundation. The Keck grant provided software and some faculty training, and also the funds to construct a state-of-the-art digital classroom. Equipped with high-end Macintosh computers with cinemascope monitors, and three back-projection screens for both digital and analogue images, the facility has become the testing ground for many of the project's ideas. Finally, the Hewlett Foundation's grant to Ithaca College has funded release time, software training and student collaboration. Most importantly, throughout the entire project I have benefited enormously from the collaboration of Professor John Barr of Ithaca College's Math and Computer Science department, whose expertise in Macromedia Director has enabled the creation of prototypes of the finished project.

Before any aspect of the project could be implemented, however, I needed to acquire the raw material for our work: the images in and around Chartres Cathedral that would form the basis for the panoramas and other views of the finished project. This required two trips to Chartres, the first using a traditional 35 mm camera for slides that were also scanned onto CDs, and the second using a relatively high resolution digital camera. Both trips required the use of a special tripod head, which held the camera in place for the panorama shots, and rotated the camera every 20 degrees, for a total of 18 shots per panorama sequence.5 The use of a 24 mm lens meant that the panoramas would cover as much vertical view as possible, without significant distortion.

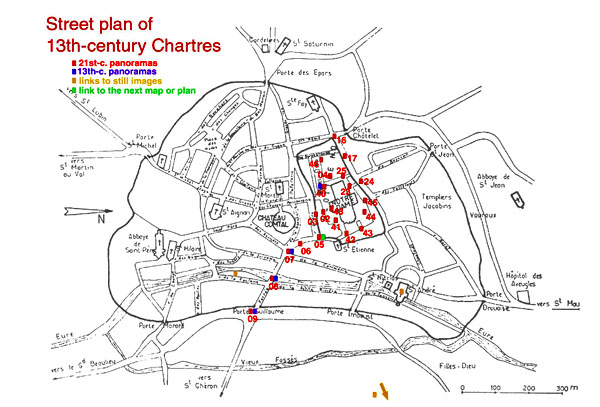

Fig. 1. Street plan of 13th-century Chartres

Before each trip, I plotted the location of panoramas on a 13th-century street plan of Chartres, as well as on plans of the cathedral itself and its immediate environs. My goal was to construct at least two panorama pathways leading from former gateways through the city wall to the cathedral. Each pathway proceeds along medieval streets and through the wall that once separated the cathedral cloister from the rest of the town (Fig. 1). I have also shot panoramas completely around the cathedral, and in front of each one of the three sets of portals. Finally, I shot interior panoramas – the most difficult to shoot because of lighting conditions – to provide complete coverage of the cathedral's interior spaces. Many additional 'still shots' were taken of all of the important imagery outside and inside the building, including shots of each ground-level stained glass window, and shots of all of the sculpture on the outside of the building. Finally, I shot and sometimes manufactured a number of 'textures', which are such images as half-timber architecture, rough stone masonry, fortified walls and gatehouses, and even pollarded trees, both in Chartres and elsewhere, to serve as the material for transforming the panoramas into 13th-century versions. With 18 images per panorama, 47 panoramas, and several panoramas that had to be shot two or three times, I have over 1,600 images of the cathedral and the town. QuickTime VR Authoring Studio software, which runs only on the Macintosh platform [ed. note] , creates each panorama out of the original 18 images, and also creates an underlying image file that can be manipulated in Adobe Photoshop.

The next phase of the project involves researching primary and secondary sources for evidence of the original appearances and spatial layouts of the cathedral and its urban setting, and evidence of political, social, and economic transactions with a direct bearing upon how the cathedral might have been experienced in the 13th century. Some of this evidence is visual: black and white photographs survive of the Porte Guillaume gatehouse before it was demolished by the Germans on their way out of Chartres in 1944. Other research taps into the archaeological record. For example, the 13th-century choir screen, or jubé, no longer survives, replaced in the 16th century by the screen that currently separates the ambulatory from the altar area. The screen separating the choir from the nave has vanished completely, conveying a sense of openness and easy access that never existed during the Middle Ages. Based on fragments that have been recovered, and comparisons with other 13th-century choir screens, it is possible to reconstruct plausibly the appearance of Chartres' 13th-century jubé.6 Finally, urban histories of Chartres and the surrounding region provide insight into the social practices and physical environments within the 13th-century town,7 including evidence of the economic and political tensions between the cathedral's chapter and the Count of Chartres, which affected how the cathedral was used, and the kinds of images included in its stained glass.8

Fig. 2. 21st-century panorama of Chartres

It is one thing, however, to acquire an intellectual sense of what something looked like in the 13th century; it is another to attempt to recreate these appearances digitally, especially when one is trained as an art historian rather than as a graphic designer! Using Adobe Photoshop, some student-workers and I have tackled the steep curve of learning how to revise existing panoramas to match what might have appeared in the 13th century. Photoshop provides a variety of ways of layering both subtle and large-scale adjustments and applying both pre-set and imported textures over existing images. Fig. 2, for example, is the image file that represents the 21st-century panorama just outside the Porte Guillaume, scaled to one-tenth its actual size. To transform it, the 1944 photo of the gatehouse was resized and reoriented, and placed in approximately the position it occupied in the late Middle Ages. Then textures were layered on top of this gatehouse, to give it the proper colour and appearance (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Gatehouse with texture layers

Next, using existing sections of the medieval wall still partially standing elsewhere in Chartres, a new curtain wall with bastions was constructed. The process was laborious, because it required careful layering of textures at precise angles to match the viewer's perspective; the borrowing of certain elements, such as the hoarding, from other locations; and the creation of yet other elements, such as the crenelation on top of the bastion towers, from scratch (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. Created elements: crenelation on top of the bastion towers

I also replaced the modern urban sprawl on the bank of the River Eure opposite the medieval town with flat farmland. A single half-timber building is added to evoke the isolated nature of architecture outside the medieval city walls. Finally, although they by no means appear as they will in the finished version, two soldiers, heraldic banners, and roofs from the long-destroyed castle of the Count of Chartres are placed as overlays on the panorama (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5. Castle of the Count of Chartres with overlays

In the finished project, these elements will serve as focal points for virtual interactions, allowing students to experience some of the political and economic factors that influenced a pilgrim's understanding of Chartres and its cathedral. The result, while not, at this point, 'factual', nevertheless provides a plausible 13th-century view, and serves to dramatize the difference between this visual environment and the setting we experience seven centuries later.

The cathedral's interiors present similar challenges: although the structure remains largely intact, numerous additions and changes in practice have altered considerably the physical environment that would have enveloped a medieval pilgrim. Today chairs fill both transept arms and the nave. In the 13th century, there were seats only in the choir for the clergy, the chapter, and their invited guests.9 The bulk of those attending mass at Chartres either stood on the cold stone floor, or rested against a few bales of hay strewn about. A student has partially completed the job of removing the modern chairs, which requires careful reconstruction of some of the pier bases. A greyed-out area reveals the location of the medieval choir screen, which would have blocked the view into the crossing area. At a point near the famous 'Belle Verrière' stained glass window along the choir ambulatory, a modern glowing glass sculpture and informational posters have been erected, competing with the light from the stained glass windows. In addition, the 16th-century choir screen provides a flowery sculptural character completely at odds with the 13th-century screen. I have begun the process of transformation by eliminating the glass sculpture, and inserting the individual shots of stained-glass windows into their locations within the panorama, to simulate 13th-century lighting effects. A prototype of the 13th-century choir screen has replaced a section of the 16th-century version, dramatically illustrating how the 13th-century visual environment within the ambulatory differed from what we see today.

The last of the concurrent project phases is the creation of interactive interfaces that will allow students to explore both the 21st- and 13th-century versions of the panorama and related imagery. Using Macromedia Director, which can seamlessly integrate a variety of media, and provide a means for viewers to experience these media interactively, John Barr and I have begun the process of creating two different 'virtual pathways' through the cathedral and its urban setting. We have yet to concern ourselves with the final 'look and feel' of the design interface, and much of the textual material is only a preliminary draft. Both versions of the project will begin at the same location: approaching the town from the wheat fields outside of Chartres, gazing at the distant cathedral.

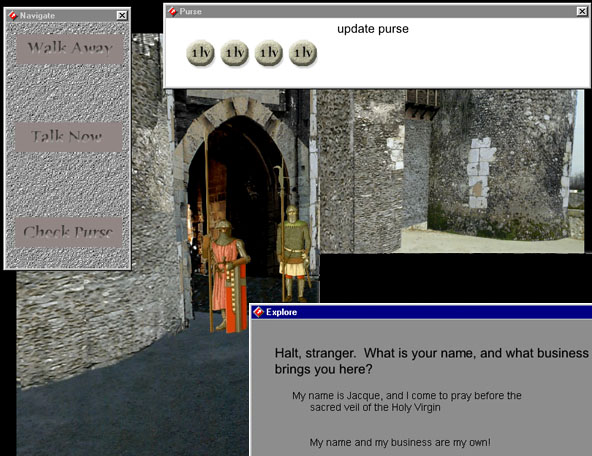

Fig. 6. The first pathway – the 'virtual discovery tour'

The first pathway – the 'virtual discovery tour' – seeks to place students in Chartres as it currently exists (Fig. 6). A series of 'hotspots' will be created within each 21st-century panorama; these hotspots activate different buttons off to the side of the panorama. These buttons, in turn, activate a set of images and a series of questions designed to focus students' attention on particular issues related to that part of the panorama. A hotspot by the remains of the Porte Guillaume, for example, will lead to a set of images and diagrams of gatehouses, and a series of questions that will prompt students to consider how the Porte Guillaume might have functioned in the 13th century. An 'inventory' keeps track of the number of hotspots visited by the student, and will not allow them to proceed to the next panorama until they have visited all of the hotspots. The hotspots are signaled only by a change in the cursor's shape; the goal is to force students to explore the entire panorama with their own eyes, and not to focus them on only a few select images, as in the traditional classroom presentation. Additionally, an illustrated timeline will provide students with an historical context in which to place their experiences. A map will allow the student to keep track of where they have been, and to return to prior panoramas. Once a student has navigated all of the hotspots offered by a panorama, they can proceed to the next.

The second pathway, which sends students back to the 13th century, will be much longer in the making, since it requires a full set of 'transformed' panoramas, which are very time-consuming to create. Once finished, however, this pathway will be characterised by a total immersion into a 13th-century visual environment. A student will enter the 13th-century experience through a door in the lower right-hand corner of the computer screen. Once the door opens, students will find themselves confronting a panorama with computer-generated 'visual aids', such as buttons or arrows. The intent is to ensure that students explore and interact with the panorama as if they were actually standing in the location represented by the panorama, rather than experiencing the image through an interface outside of the image. By exploring the panorama with their cursor, and interacting with the various hotspots that will eventually confront them, students will simulate the randomness of actual experience. The interactions themselves will force the students to confront the kinds of experiences that would have faced a pilgrim in the 13th century. For example, upon reaching the Porte Guillaume, a pilgrim would probably have been forced to deal with those guarding the entrance to the city, and would have had to pay an 'entrance tax' before being allowed to continue on their journey. Professor Barr and I are in the process of constructing a dialogue with one of the soldiers outside the gatehouse. This dialogue will require students to pay the fee out of their own 'virtual purse', and will confront students with the knowledge that the Count of Chartres, not the cathedral, controls access to the streets leading to the cathedral (Fig. 7). Similar interactions will be constructed for the other soldier, the heraldic banner, and the distant view of the Count's castle; all of these images are intended to spark visual thoughts and evoke culturally-determined beliefs in the mind of our 'virtual pilgrim'.

Fig. 7. The 'virtual pilgrim' experience

The project is, obviously, a work in progress; indeed, the time-consuming nature of the work has caused me to re-evaluate the project's goals. What has become evident is that the collaborative work itself, both with professionals in other disciplines – such as a computer scientist – and with students, is not simply a means to an end, but itself one of the fundamental benefits of the project. Art history has always relied on technology in its teaching and scholarship; in fact, the advent of slide projectors, and their side-by-side placement in the classroom, fundamentally shaped the way we present art history to students and to each other.10 Yet many art historians are either reluctant to embrace the digital image, or instead simply use digital images as substitutes for slides. Collaboration with a professional who must, by the nature of his profession, embrace new digital technologies has forced me to confront the ways in which technology can be used not simply to replicate the existing structures of our discipline, but rather to reshape the very substance of what we teach, and the means by which students access and interact with that substance. Additionally, the collaboration with students has provided them with valuable 'hands-on' learning experiences that integrate study of architectural history with education in digital skills that will be very useful to them in the marketplace, a factor that, regrettably, art historians have traditionally shied away from considering.

Obviously, the impact of this project upon how students learn architectural history cannot yet be judged. I have made preliminary attempts to shape interactions between my students and the 21st-century panoramas, centered on questions that require them to evaluate the experience as it unfolds. The sense of active participation and discovery within the classroom is palpable. At the very least, the substitution of panoramic images for static, two-dimensional images provides a sense of space and continuity, and allows students to explore a complete visual environment at their own pace, rather than being handed a limited and predetermined set of images. The addition of interactive hotspots opens the potential for a fully self-guided, exploration-driven, and hands-on educational experience. If, in the end, the project can provide a plausible simulation of the physical environments and social transactions a 13th-century traveler to Chartres might have experienced, and at the same time allow students to 'learn by doing' rather than 'learn by listening', I believe the effort behind the project will have been worthwhile.

November 2001

Notes

1. Calkins, R. (November/December 1995), "The Cathedral as Text," Humanities, p. 35.

2. See Erlande-Brandenburg, A. (1994), The Cathedral: The Social and Architectural Dynamics of Construction, trans. M. Thom, pp. 269-77. Cambridge and New York, 1994: Cambridge University Press.

3. See generally Pointon, M. (1997), History of Art. A Students' Handbook, 4th ed., p. 42. London and New York: Routledge; Minor, V. H. (2001), Art History's History, 2nd ed., pp. 25-26. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall, Inc.

4. The site is located at http://www.learn.columbia.edu/Mcahweb/index-frame.html. For a book that treats Amiens cathedral fully within its social context, and deals also with the modern experience of the cathedral, see Murray, S. (1996), Notre Dame, Cathedral of Amiens: The Power of Change in Gothic, Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press.

5. For panoramic tripod heads, see http://www.kaidan.com/products/pano-prods.html.

6. See generally Mallion, J. (1964), Chartres: le jubé de la cathédrale, Chartres: Société archéologique d'Eure-et-Loir.

7. See, e.g., Chédeville A. (1973), Chartres et ses campagnes (XIe - XIIIe s.), Paris: Editions Klincksieck; Michel, M. (1984), Développement des villes moyennes: Chartres, Dreux, Evreux, Paris: Publications de la Sorbonne.

8. For a discussion of how stained-glass imagery at Chartres reflect the 13th-century social structures and political turmoil within the town, see Williams, J. W. (1993), Bread, Wine, & Money: The Windows of the Trades at Chartres Cathedral, Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press.

9. See Merlet, L., and de Lépinois, E., "The Charter of 1221 Concerning the Rights of the Cantor over the Choir Stalls", Cartulaire de Notre-Dame de Chartres 2, pp. 95-96, translated and reprinted in Branner, R., ed. (1969), Chartres Cathedral, pp. 97-98. New York and London: W.W. Norton & Co.

10. See generally Bailey, C., and Graham, M. (1999), "Compare and Contrast: the impact of digital image technology on art history", Proceedings of the 1999 Conference on Computers and the History of Art, http://www.chart.ac.uk/chart1999/papers/bailey-graham.html

Editor's note: a number of similar products which run on other platforms are also available.