CONVERGENT PRACTICES: New Approaches to

Art and Visual Culture

|

|

CONVERGENT PRACTICES: New Approaches to

Art and Visual Culture |

Irina D. Costache, California State University Channels Islands

Visual Culture/Virtual Art 1

Keywords: art history, e-teaching, blended learning, electronic resources[D]arkness, [he thought], was nothing other than the simple absence of light. Now, on the contrary, here he was, plunged into whiteness, so luminous, so total, , that it swallowed rather than absorbed, not just colors, but the very things and beings thus making them twice as invisible.

Jose Saramago 2.

The brightness of slides illuminating the darkened lecture hall, a common expectation of art historical presentations, has ‘swallowed’ the originals they aimed only to represent and has made the photographic replica synonymous with authenticity. ‘This painting by Picasso,’ a typical introduction of a work on a screen or accompanying glossy reproductions in books, is a statement that has equated the simulation with the original and, by concealing the implications of using surrogates, has elevated the copy to the value of the ‘real thing’. The recent announcement that Kodak will cease the production of slide projectors had sent shockwaves through at least part of the art history community. Those who have moved beyond this modernistic, but antiquated, technology are indifferent. Others, for a variety of reasons, including economic, are terrified. The fear that slides and slide projectors will no longer support the teaching of art and its history reveals the astonishing implications this technology has had in a very short time. This process of visualisation, in place for less than seven decades, has not only substantially altered and re-contextualised the art discussed, but has also established practices unchallenged in the last half century, which now, when they are being displaced, have been called into question.

Even though art history is inherently interdisciplinary (and this is overtly exposed by its semantic designation), it has isolated itself from fields outside the humanities and even from certain visual components of culture. This segregated path has been reinforced by the distrust with which modern western art history has perceived the interaction between art and technology, conveniently ignoring that key visual and theoretical concepts (such as perspective, golden rule, proportions, etc.), are based on mathematics, geometry, and science. In a similar fashion, photography, film and more recently, television, and video, even though perfect voices for modernity, have been marginalised and have yet to find their rightful place within the (modern) history of art. The accessibility of technology, its mass appeal and heterogeneous usage have contributed to its dismissal in a discourse defined by exclusiveness and originality. The possible duality of new media, documentary tool and visual language, actively explored by artists and passively employed by art historians in a variety of photographic material including slides, has been problematic for a field based, at least on a superficial level, on binary opposition. The electronic media and virtual environment have only augmented the visual and theoretical ambiguity and complexity facing art and its history in this new century/millennium. The late 20th century rapprochement between ‘high art’ and popular culture and between western tradition and global artistic views has further accentuated the isolation of the existing operational framework of art history. The slide projector is more than a tool of the past. It is a metaphor of nostalgic links with a linear, reductive, rigid, and self–reflective art history.

At the dawn of a new millennium searching for novel practices is part of a somewhat obligatory, yet meaningful project of reconciling the (familiar) past with the (unknown) future. However, converging art (historical) practices are not easily forged and artists more so than art historians have been successful in testing new and heterogeneous grounds.

The transgressive boldness with which Duchamp’s ‘mechanical version’ of Mona Lisa and Allen Toney’s 1995 electronic work Voice of the Wheel 3 link themselves with the Renaissance and Baroque, establish an unsettling dialogue between familiar masterpieces and modern means of creation and expression. Positioned at the opposite chronological poles of the 20th century, these works use mixed and innovative processes, which operate as modifiers of existing discursive, cognitive and performing practices. The seemingly recognisable imagery obscured and, at the same time, heightened by the novel conceptual implications and the artists’ ironic and iconic references to the past, made possible by contemporary technology, disclose the deceptive fallacy of giving validity to images based on habitual art historical interpretations. Using technology not only as a transparent supportive medium, but also as a focal element of enquiry, these works expose practices that have turned passive ingredients into active components of the visual field. The images continue to undergo additional transformative processes, outside the original creation and intentions of the artists, when they travel through technological and virtual journeys. This includes, in addition to slides and other mechanical reproductions, the now commonly used electronic operations of downloading, copying, scanning, e-mailing, etc., which transport the copies even further away from their original sources. These alterations although easily ignored, once revealed, could either restore superficial visuality as an epistemological end, or trigger a new path of enquiry and question the faith invested in visual appearances as unique proof and generator of authenticity. While art has experimented with new modalities of visual enquiry, art history, the discipline investigating this field, is still defined by and within traditional formats.

Fig. 1. Virtual Space: the Abundance of Resources.

Art historical analyses continue to be based on traceable textual and visual genealogies with climactic moments and concluding statements supported by table of contents, indexes, bibliographies, etc. The unalterable closure and finality of published material, which gives both the topic and author an authoritative position, solidifies the credibility of this process. The internal dynamics between the well-argued thesis with proofs and supportive ramifications of notes and appendices isolate the content of analysis from exterior links and create a trajectorial coherence, which establishes the supremacy of a sacred and pristine space of art with a capital A. This structured nature of art history scholarship is antithetical to the open-ended and non-linear journeys of ‘hunting’ (searching) and ‘collecting’ (bookmarking) of the web. The abundance of images and art historical resources competing for attention and examination in virtual space is overwhelming. The recognition that it is impossible to see or read it all, distances the virtual format even further from the paradigms of art historical practices (Fig. 1). Unique archival resources, complete references, exhaustive and up-to-date bibliography are, paradoxically, on the one hand easier to achieve, due to the extraordinarily efficient programs, but on the other impossible to expect in an (electronic) environment of continuously fluctuating information. The possibility of stumbling upon unexpected extraordinary things in a matter of minutes and spending hours arriving at the nothing, a major trait of the medium, involves a high level of randomness and puts an emphasis on the journey rather than the final destination. The temptations of hypertextuality, randomly connecting and disconnecting familiar meanings and values, divert the search away from its initial scope and contaminate the homogeneity and purity of the art space. (Fig. 2) The heightened role of anonymity, erasure, interactivity and collaboration threatens, redefines, neutralises, and even displaces in virtual space the meaning of transcendental geniuses, eternal masterpieces, and unique experiences and reinforces an interpretation contradictory to the validated paradigms of art history.

Fig. 2. Virtual Space: Redefining the ‘Art Space’

Within cross-chronological and cultural contexts these characteristics are not new. But rather than looking at existing models (such as the temporality of Native American sand painting, the performative nature of Japanese or African art, the anonymity of medieval art and the value of process in conceptual art, all of which have offered effective alternatives to the notion of art as the sum of master and masterpiece), the new media have been, again, reduced to tools and subordinated to the higher ‘cause’ of art. The inert usage of electronic and web-based (re)sources for reproductions, libraries, databases, archives, e-mail and list-servs and the translation of the virtual environment into ‘palpable’, and ‘findable’ proof manifested by the eagerness to download, desire to print and need to bookmark, confirm that the complexity of the virtual space has been limited to its interface. The screen, the fragmentary visualisation of a multi-dimensional structure, has become an end product and a self-sufficient two-dimensional field. The lack of new paradigms, evaluating modalities, and selection criteria for this medium is also evident in the connection virtual projects aim to establish with recognisable ‘brick and mortar’ institutions. Virtual art and culture will require a ‘reconfiguration of the meaning of art, of aesthetics, of artists’ relationships.’ 4 ‘It’s time,’ Barbara Stafford also argued wider ‘to craft new methods, invent new subjects, launch other initiatives.’ 5

A perfect example of the uncertainty and ambiguity with which art and its history are operating in the virtual ream is the exhibition 010101: Art in Technological Times. 6 Developed by San Francisco Museum of Art and open online on the first day of this new century, the exhibition, and its symbolic title, aimed to realign the identity of art and its dialogue with technology. ‘Most of the digital artworks in the 010101 exhibition are as visually appealing as they are conceptually intriguing,’ states Matthew Mirapaul in his review. ‘But be prepared: a fast internet connection will help reduce the time it takes to view the works and visitors must learn to navigate the exhibition’s complicated user interface.’ 7 Jason Spingarn-Koff also recognises the complicated and time-consuming journey ‘requiring users to download plug-ins, wade through cryptic interfaces, and read curators' texts before accessing the Web-based art’ 8. The exhibition has specific technical requirements: Shockwave and Internet Explorer 5 or Netscape 4 and a Macintosh G3 processor or higher, 128Mb of RAM or higher, high-resolution screen, and cable or DSL connection. Four years later these technological parameters are hardly a novelty and at the reach of most computer users. In contrast, the artistic structure of the show is still a novel concept, outside the ‘mainstream of contemporary art history.’ The exhibition clearly reveals the discrepancy between the pace of developments in art and technology and the crucial role of specialised support to create, access, and examine such works. It may be the dependence on computer specialists that makes art historians fearful that they could loose control over art. This unfounded view speaks more about the protective divisions between disciplines, the elitism of art history, the lingering suspicions of collaborative processes, and the difficulty of accepting the familiar from new perspectives. (The restoration of the Sistine Chapel is a case in point.)

Dismissing the value of understanding the rules of the virtual environment established by hardware, programs, servers, software, skills, passwords, protocols, copyrights, permission, databases, licensing, has curtailed the art historian’s ability to explore the incredible possibilities of the medium. The continued distrust of electronic-based scholarly activities and the preservation of traditional print or oral formats even in this new environment confirm that converging practices compatible with the ‘new set behaviour, ideas, media, values and objectives’ recognised by Roy Ascott 9 over a decade ago, are very slow in coming.

The educational arena, even though often perceived as a follower in the field rather than a leading force, has embraced the virtual environment and has been an active and fertile ground for investigation of both teaching and art historical practices in the novel arena of visual culture and virtual art. I have been fortunate to work with individuals and within departments supportive of innovative teaching both in form and content. I am presently an art historian at California State University Channel Islands (CSUCI), one of the newest four-year colleges in the USA, where my colleagues and I have outstanding support from the university to experiment with electronic media and develop new modalities of teaching and interdisciplinary enquiries. These new approaches have been embraced by students and have proven to enhance their learning.

CSUCI only has a web-based digital image collection. No need for nostalgia or long good-byes. Most classrooms are equipped with PCs or Macs linked to data projectors and VCR or DVD and with live Internet connections. 10 This extraordinary high tech environment is a unique opportunity for an art historian to reflect on the past and future practices of the discipline. In addition, the online teaching software provides the technical platform not only for the convenience (and burden) of having remote access 24/7 to the course content and information, but also for enhancing the learning process. The transition at the institutional level has been seamless. On a personal level it has been a complex, but very rewarding journey. To arrive at hybrid modalities that are not just about technological hype requires a serious visual and theoretical evaluation of known paradigms and a thoughtful, on-going process of understanding the possibilities offered by electronic media. The converging practices I have developed and continue to explore use new media not only as a convenient instructional tool but also, and more importantly, as a key element of visual and theoretical enquiry. Expanding experiences beyond traditional formats and environments gives art and its history a greater sense of meaning within the diverse cultural and technological panorama of today.

In the next segment of this paper I will discuss some of the hybrid projects I developed for teaching and presentations of art historical material. The goal of these innovative modalities is to maximise the attributes of each medium and to establish converging practices that meaningfully connect past strategies with new ones to enhance knowledge and learning.

Webography

Webography (an annotated bibliography of web resources) is a project I recently developed which has several objectives. First, its aim is to familiarise students with the wealth of information about art available in the virtual environment. Secondly, the project provides ways of teaching traditional research skills and develops methods for evaluating internet sources. Finally, webography offers the opportunity to link traditional library resources and practices with electronic ones. For the project the students have to research the web and create an annotated list of about twenty-five sites (submitted over the period of the semester usually in sets of five). Each entry has to include a very brief description of the sites and a rating of visual (V) and textual (T) content using the scale 5-1 (five being the best). The lists are posted to Blackboard (the teaching software used by CSUCI) and available to the entire class.

This type of project generates a substantial list, which students, working with the library, learn to integrate within the library catalogue system. For example, when searching for Mary Cassatt in the library, the results will include, in addition to books and other sources, the sites selected by the students, linking in the most effective way traditional resources with virtual ones. Students learn a great deal from this project. They realise that there is an enormous amount of information in virtual space and that its validity is not easy to evaluate. Overall the project triggers an interest in research and the need to integrate traditional art historical tools with new ones.

Example:

(the course was Women and the Arts - the class had 9 students)

Current Forum: Web Lists (Webography)Read 9 times

Date: Thu Feb 13 2003 4:12 pm

Author:

Subject: Sites pertaining to Woman Artists. (LIST 1)

------------------------------------------------------------------------

http://junior.apk.net/~fjk/women.html

The role of woman in Greek art T5, V3

This is a great site for content. It talks about everything from how woman [sic] were treated in general and with regards to their art.Current Forum: Web Lists (Webography) Read 9 times

Date: Wed Feb 12 2003 6:57 am

Author:

Subject: The Varo Registry of Women Artists

------------------------------------------------------------------------

http://www.varoregistry.com/

The Varo Registry of Women Artists

This site is full of links to full-page sites featuring women artists. The only drawback I found was the fact that it appears to be a registry in which only newer contemporary artists are listed. I enjoyed the resume and personal statements.

V3, T5

Current Forum: Web Lists (Webography) Read 10 times

Date: Wed Feb 12 2003 10:43 pm

Author:

Subject: List #

------------------------------------------------------------------------

http://www.uwrf.edu/history/women.html

Women Artists through time

Actually titled 700 important women artists 9th-19th centuries on the first page… It is a wonderful site with many images.Electronic guest speakers/ lecturers

Another mode in which traditional practices can be intertwined with virtual possibilities and add new voices, views, and topics to the course content is e-guest lecturers. This allows speakers to share their expertise and knowledge and interact with students and faculty via the web, expanding the class beyond its schedule by fully utilising the flexibility of the virtual space. (See time and day in the examples below). Participating in the project last fall was Jeffrey Cunard, a partner in the international law firm Debevoise & Plimpton, who practices in the area of intellectual property (copyrights and trademarks) and information technology and also serves as counsel to the College Art Association. The specific topic of this project was VARA (Visual Artists Rights Association) and its implications for contemporary art. Students were assigned web-based readings and PowerPoint presentations on this topic and asked to post to the entire group their questions and comments. The entire project took place over a period of three weeks. Jeff Cunard was very generous with his time and provided not only extensive and thorough answers, but also, being directly involved with these issues, was able to illustrate his comments with specific cases. (See excerpts below). (This class had 13 students.)

Current Forum: VARA Read 25 times

Date: Sun Nov 16 2003 6:36 pm

Author: student

Subject: Questions about Implications of VARA

After having reviewed the material on VARA, I was pleased to see that the rights of contemporary artists are protected to the extent shown by VARA.

1) What if someone were to commission a site-specific work of art and after a period of time, wanted to replace that piece of art and had not obtained a waiver from the artist and the artist was uncooperative?

2) What if someone purchased a property with a site-specific piece of art and their sensibilities were offended by this artwork and they wanted to remove it?

3) What if an artist submitted a design that was approved and then in the process of installation deviated from the approved design and this were to be critically acclaimed. What rights would the property owner have in this case?Current Forum: VARA Read 18 times

Date: Wed Nov 19 2003 4:42 pm

Author: cunard, jeff

Subject: Re: Questions about Implications of VARA

------------------------------------------------------------------------

Thank you for yet another thoughtful set of questions. Here goes:

1) Well, it depends on whether the artwork was a mural (affixed to a building or not). Let's assume not, and that the sculpture is a free-standing sculpture for a public park, made pursuant to a public works commission by a city. If the work is merely removed to another location, there is no destruction, so the city can do that without violating VARA.2) With respect to a purchaser's decision to remove a work, the answer is

the same as above. However, after 1990, the purchaser cannot destroy the

work (assuming that the sculpture is of recognized stature). Again, if the work is affixed to a building, different rules apply, that are more favorable to the building owner.3) I think no rights under VARA would accrue (to the artist or the property

owner) with respect to the artist's variation of a design after the approval

of the commissioning party but before actual delivery of the sculpture.At the end of the semester Jeff Cunard and I discussed the outcome of this experimental project and agreed that adding a live discussion via video conferencing to allow students to interact more directly with the e-lecturer would further enhance the dialogue. I will continue to invite e-lecturers to my courses and explore ways to add new features to this very valuable type of project.

Museum field trips

The museum field trip, an essential component of art history courses, is perceived as the chance to finally fully experience the masterpieces. I always took a critical approach to these visits asking students to reflect upon the entire experience, the narrative of the institution and the dialogue it establishes with the audience, rather than focusing solely on art. The development of websites for museums was the perfect ground for starting a critical and comparative examination of art history practices and modalities of creating, analysing, and disseminating art in this new media environment. In the last three years I have developed cyber museum field trips and continue to explore this hybrid modality of using the virtual space as both a tool and object of enquiry. The cyber field trips are homework assignments. The students receive a series of questions to focus their attention on the cyber journey and this new way of experiencing art. An additional concern of the assignment is to expose them to the global nature and possibilities of this medium, by visiting museums on different continents. The project encourages students to do their web searches in various environments (at home, at the university library, etc.) and reflect upon the influence these external factors have on how art is viewed in virtual space.

The paper students have to write in connection with this assignment makes them further reflect upon the way in which the virtual space is linked to visual culture and museums. Using the field trip to a real museum (usually the Getty) as a starting point and comparative resource, students have to reflect on a wide range of issues related to the virtual and visual space of the museum, such as: the purpose of museums’ websites (ads or replacement or the real museum); the dialogue the website establishes with the audience; the benefits (such as information, education) and drawbacks of the virtual environment; the changing role of the viewer; the transparency (or lack of) cultural identity in virtual space, etc. (Fig. 3). Students’ responses to this project has been very positive. Not only were they amazed by the enormous amount of museums on the web, but again, they developed ways of researching sites and discerning the validity of their claims.

Fig. 3. Museums and the Web

During the spring of 2004 I am adding an international component to the cyber field trips. Students enrolled in my course will exchange via the web their views about museums in cyberspace with their colleagues in Florence. The specific focus will be the Getty and the Uffizi and involves the collaboration of Elliott Kai-Kee from the Getty and Giovanna Giusti from the Uffizi Gallery.

Electronic course packs

The virtual environment can be used for other hybrid modalities made possible in the last few years. One of these possibilities is electronic reserves of both textual and visual material. The password protected information allows not only a wide range of material to be electronically available, but also provides the convenience of literally instantly updating a class reader with the most recent, last minute information. In addition, the ability to archive all e-reserves makes it easy to access and review the material for use in other courses.

It is evident from these examples that collaborations are key to the development and successful implementation of these novel hybrid projects.

Visual presentations

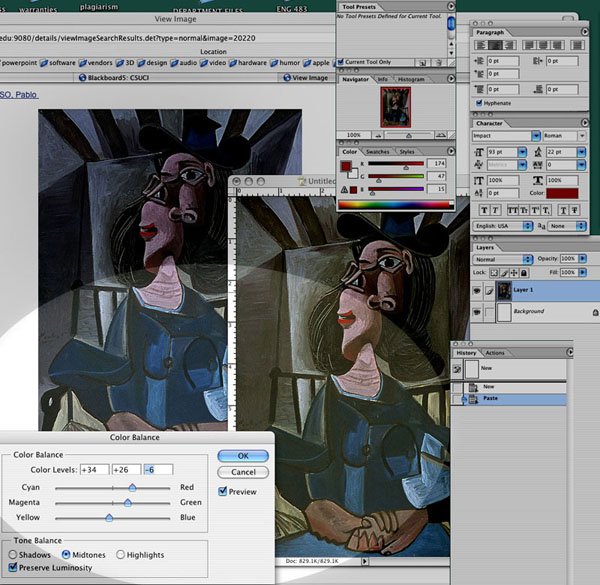

No current discussion about converging practices in art history can exclude the changing format of the presentation. The parallels between traditional slides and their virtual counterparts are easy to perceive. However, the essential distinction between the physicality of slides and digitised images has not been effectively used. The electronic medium requires only one image, which, with proper protocols in place can be shared with an infinite number of users. Yet, institutions across the globe are digitising the very same images, instead of finding a way to streamline this process. As electronic images are becoming more widely used it is important to remember that they are still reproductions no matter how appealing they can be and how ‘zoomified’ they can get. There is in fact, a greater potential and temptation for adjusting virtual images, making them nicer, crisper, cleaner. This process disassociates the virtual copy even more from the original, as the sources for these rectifications are one’s memory of what ‘looks right’ or, in the best case scenario, another reproduction, and rarely, if ever, the original. (Fig. 4)

Fig. 4. Electronic Images: the Temptations for Adjustments

The delivery of virtual images in lectures also raises a series of novel issues. The arbitrary side-by-side comparison can be replaced by a wide range of possibilities: a set of three, or four, or even more and include text, music, and moving images. Most programs permit ample manipulations to produce very slick presentations. I discovered that what used to be a rapid arrangement of slides based on my lecture notes has become a very seductive process with incredibly tempting possibilities. The routine, neutral, and rigid placement of slides in the carousel has become a hypertextual, work-in-progress project (Fig. 5). Learning various programs gave me on the one hand a sense of empowerment: the (virtual) visual world was within my (electronic) reach! On the other it gave me a feeling of ‘de-powerment’ as I quickly realised that the seductive formal appeal of the virtual space has the ability to ‘swallow not just colors, but the very things’ making the content of the lecture ‘twice as invisible.’

Fig. 5. ‘Behind the Scenes’ of Virtual Presentations

This painting by Picasso remains a typical introduction to a work projected digitally. The image, now enhanced by electronic qualities and with an unprecedented mesmerising appeal, erases its links to the original even more effectively than before and can easily shift the attention from the work to the superficial visual attributes of the interface. The use of the virtual space only as an electronic substitution for mechanical reproductions can produce extraordinary ‘high-resolution visual packages’ which will further diminish, distort, and even reverse the differences between the original and its copies and produce little change in art historical practices. However, digital presentations that use mixed processes and heterogeneous sources, unexpectedly and simultaneously present on the same screen, can not only transgress beyond the traditional slide format but could also substantially enhance the visual and conceptual information and art historical enquiry. It is this kind of project I have developed in collaboration with the multimedia staff at CSUCI. Comparisons between juxtaposed moving and static images, linking the slide show to virtual tours, cross-disciplinary connections, impossible until now in art history, have operated as modifiers of existing practices and exposed some of the possibilities of the virtual space. These hybrid modalities make use of the continuous fluidity and developmental attributes of the medium and displace the limitations of the stagnant isolation and ‘ivory tower’ homogeneity of art. These novel practices facilitate a comprehensive interdisciplinary dialogue that includes not only technology but also other disciplines and components of visual culture. However, such projects are difficult to disseminate in traditional formats and cannot be expected to conform to the evaluating patterns of existing practices.

Linking traditional practices with the new identity of the virtual environment requires significant conceptual and visual transformations. Ironically art history has been more effective in writing about the avant-garde than assuming this stance. In this era when ‘artophiles,’ ‘bibliophiles,’ and ‘technophiles’ merge into unified identities reassessing art historical practices does not imply an abrupt abandonment of the past. Rather, as discussed here, the idiosyncrasies of new media should be incorporated in a comprehensive examination of visuality. New modalities of critical analysis will have to reconcile the monolithic, homogeneous and tangible aspects of traditional art and art history with the pluralistic, heterogeneous, and immaterial attributes of virtual space. These practices will have to develop and accept cognitive and aesthetic validations based not only on progressive development and predictable continuous trajectory leading to climactic closures but rely also on hypertextual patterns, hypothetical approaches and open-ended systems. ‘We must begin by distinguishing, Plato wrote, between that which is and never becomes, and that which is always becoming and never is.’ 11

November 2003

Notes

1. This paper is a revised version of the presentation given at the 19th annual CHArt conference in London, November 2003. The visual material was also revised for publication. My presentation included over thirty digital images, some of them comprising superimposed works, with several screens opened at the same time and juxtapositions of images, music and film. I would like to thank Tom Emens, multimedia specialist at CSUCI, for his technical support.

2. Samarago, J., Blindness, New York and London: First Harvest Edition, Harcourt, Inc., 1999, p. 6. The author is the winner of the 1998 Nobel Prize for Literature.

3. Allen Toney’s work can be found at http://webpages.marshall.edu/~jtoney/prints-all.html (27 October 2003).

4. Rush, M., New Media in the Late 20th Century Art, London: Thames and Hudson, 1999, p. 216.

5. Stafford, B., Good Looking, Cambridge and London: MIT Press, 1996, p. 202.

6. The show can be found at http://010101.sfmoma.org/ (27 October 2003).

7. Mirapaul, M., Museum Mounts Show in Cyberspace, http://newsgrist.net/ (27 October 2003). Also published in the NY Times, January 8, 2001 http://www.nytimes.com/2001/01/08/arts/08ARTS.html (27 October 2003, subscription required).

8. Spingarn-Koff, J., 010101 Art For Our Times, http://www.wired.com/news/culture/0,1284,41972,00.html (27 October 2003).9. Ascott, R., ‘Is There Love in the Telematic Embrace’ Stiles, K. and Selz, P., (Eds.), Theories and Documents of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles and London: UC Press, 1990, p. 491.

10. California State University Channels Islands (CSUCI) is located 30 miles north of Los Angeles, in Ventura County, nestled against the Santa Monica Mountains, a few miles from the Channel Islands (It is not on an island!). The campus has been developed on an existing site with an architectural ensemble designed mostly in mid 20th century, which has been updated to the educational needs of the 21st century. Norman Foster is designing the new library.

11. Plato, Timaeus, 28.