Futures Past: Twenty Years of Arts Computing

|

|

Futures Past: Twenty Years of Arts Computing |

CHArt Conference Proceedings, volume seven

2004Wayne Clements, Chelsea College of Art and Design, London, UK

Computer Poetry’s Neglected Debut

Keywords: Computerized Haiku, computer poetry, cybertext, Cybernetic Serendipity exhibition 1968

‘Cyberpoetry has not been attacked. It has never been very real, and never enough unreal. Nothing has been accomplished, though variations against the normative patterns have been made, perhaps with too small a price. Cyberpoetry, as it is, will produce no martyrs, only house guests.’1

B. K. Stefans

In a recent paper presented at CHArt’s 2002 conference Lanfranco Aceti (quoting Jon Ippolito, curator of the Virtual Projects and Internet Art Commissions at the Guggenheim Museum in New York) spoke about ‘the need to preserve behaviours rather than media’.2 Aceti appears to oppose this curatorial venture.3 But whether desirable or not, what is it to preserve behaviour? Is behaviour separable from media?For me today, this is to ask why reprogram Computerized Haiku (http://www.in-vacua.com/cgi-bin/haiku.pl)? In what sense can we say we preserve Computerized Haiku by its programming? After all, little remains of Computerized Haiku, neither the hardware (the computer) nor its original program. What does remain is an essay written by one of its creators, Margaret Masterman in 1971.4 In this essay there is enough – a template for a verse structure and lists of words to fill it – to sponsor the making of a version of the work. I have, in other words, written a program that will produce similar verses to the original.

But why do this? Computerized Haiku, precisely because the program was missing, was for me to be the opportunity to conduct a demonstration. My recent research has been into instructions.5 Masterman’s essay, I realised, could be turned from description to instruction. It could be translated from a human readable account back to a machine executable program. Computerized Haiku I saw as an artwork that might be thought of as a sort of computation in Alan Turing’s sense of the word: a pencil and paper instruction that might be performed by a human ‘computer’ (that is, someone who ‘computes’) – or as a program executed by a machine.6

This might be an artwork that is the preservation of behaviours, not the conservation of things. That is what is preserved, but what is lost in this process? What are lost are the historical and material circumstances that attended the appearance of Computerized Haiku. It is these that I wish to attend to now, pointing up differences between the original version and my remaking of the work as I progress.

The Early Days

To return to Computerized Haiku is to return to the early days not only of computerised art and literature but also of computing and the still relatively new science of cybernetics. Cybernetic Serendipity, held at the Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA) in London in 1968, was the first major exhibition of computer art (although there had been several earlier exhibitions of computer graphics).7 Cybernetic Serendipity was unusual in many ways. Scientists mixed with artists and no rigid distinction was made between visual art and literature.8 In those days everything must have seemed possible and most things still to be done. Looking back from our vantage point, it is possible to observe how much is different – and what may seem the same.

If we look at my recreation of Computerized Haiku (Fig. 1) and compare it with images from the original show (Figs 2 and 3) we may note some of the differences.

Fig. 1. Screen grab of http://www.in-vacua.com/cgi-bin/haiku.plIn 1968 there was, for instance, no Internet, as we know it, there were no personal computers, no HTML with which to script web pages; and programs with which to manipulate natural languages such as English with relative ease, were only just becoming available. In 1968, computers had to be installed and accessed on site, monitors were not available and output was to paper printer.9 The two images of the haiku displayed at Cybernetic Serendipity seem to show poems hand copied on to paper and pinned to the wall. Their historical interest outweighs their slightly poor image quality.

Fig. 2. Image of installation at Cybernetic Serendipity (1968): photograph courtesy of Professor Brent MacGregor.

Fig. 3. Image of installation at Cybernetic Serendipity (1968). Photo. courtesy of Professor Brent MacGregor.Because of the word processor, we are now quite used to computers handling text. In 1968 this was not so. In 1968, computerised literature was not quite a decade old. In 1959 – quite separately – there were two initiatives – Theo Lutz, on the one hand and Brion Gysin on the other (with Ian Summerville, a Cambridge mathematician) produced what may be the earliest examples of computerised literature.

That both Lutz and Summerville were scientists is significant. So is the algorithmic basis of each of their works. Access to computers was limited for those of a more purely artistic or literary background. Lutz’s work used a random number sequence to treat a text by Kafka, whilst Gysin’s was a permutation of all the combinations of the words of the phrase I AM THAT I AM. We will see this overtly mathematical option was refused by the programmers of Computerized Haiku, Margaret Masterman and Robin McKinnon-Wood; rather they permitted the user to work directly with the program.

Masterman and McKinnon-Wood were part of a brilliant generation of Cambridge scholars that came to prominence after the Second World War. Their interests were wide, and between them, embraced scientific, literary and philosophical concerns, and much else besides.

It is important to place Computerized Haiku in the context of a wider exploration of both cybernetics and natural language computing. Both of these inform the making of Computerized Haiku.

The Cambridge Language Research Unit was involved in the development of automatic translation techniques for natural languages. As part of the Unit, both Masterman and McKinnon-Wood published articles on the subject. The techniques behind translation programs would come into use in programming Computerized Haiku, as we shall see.10

Thus Computerized Haiku cannot be viewed in isolation. It was one of several programs that responded to user input with which McKinnon-Wood was involved. One of these was SAKI, developed by McKinnon-Wood with his colleague Professor Gordon Pask. Another was Musicolour (also shown at the ICA), a light display that interacted with music. SAKI began as a program to train punch card operators, and later, typists. The program assessed performance and adapted to improve the operator’s accuracy and speed. It is the ancestor of contemporary programs to teach typing.

Thus Computerized Haiku must be seen in the context of a sustained exploration of human-machine interaction that forms continuity from practical application, through to more purely literary endeavours. Several scientific and technical strands come together here: what were then recent developments in computer hardware, new programming languages and developments in cybernetic theory.

What crucially enabled the realisation of Computerized Haiku was the availability of a computer language that facilitated the relatively easy use of a computer to write a text. That language was TRAC. TRAC stands for Text Reckoning and Compiling.

It is important to note TRAC’s significance. TRAC was designed by Calvin Mooers in 1964 ‘specifically to handle unstructured text in an interactive mode, i.e., by a person typing directly into a computer’.11 As such it marked a significant advance in the computer’s usability.

Of course TRAC, and the ‘interactive keyboard’ as Mooers called it, do not cause the appearance of computerised literature. There was a persistent interest in increasing both the ease and scope of computer use and this had continued throughout the 1950s, and carries on today. Computerised literature, therefore, is a complex development where technical improvements interplay with other determining elements.

However, to enable a computer to assist in the writing of poetry was a considerable goal of some cyberneticists. Poetry as art form in some ways enjoys a peculiarly high status.12 It is perhaps this high status that has attracted computer researchers to poetry.

The contribution that TRAC makes is that it is possible to construct a poem as you go along. This is the aim of Masterman and McKinnon-Wood’s original work. To explain this it is necessary to describe Computerized Haiku in more detail. This brief discussion draws upon Masterman’s essay of 1971.

Computerized Haiku comprises a ‘Frame’ or ‘Template’ and a ‘Structured Thesaurus’. The template is the fixed form of the poem. It looks like this:

The operator of the poem is expected to make a selection for each numbered gap in the frame from the structured thesaurus, which consists of numbered lists of words. The resulting poem looks like this:

This is sometimes referred to as a ‘slot’ system or a ‘substitution’ system. It is not the only method of computerised writing. There are also generative methods, using Markov chains or recursive grammars. These produce more complex, less predictable texts. There are also various techniques for shuffling and cutting up texts. However, the use of substitution systems is still popular,13 as is the haiku form, particularly on the Internet, where you can find many examples of its use.

To assist with composition there is also a Semantic Schema. The schema is in the form of a diagram:

Fig. 4. Semantic schema for a computerised haiku. The author’s representation of a diagram in Masterman’s 1971 essay. The lines here marked in bold were marked with an asterisk in Masterman’s diagram. Where two lines run between words only one was to be chosen.

This schema is meant to assist the operator whilst he or she fills in slots in the templates with words from the thesaurus. The idea is that the arrows ‘protect the inexperienced poet from feeding random choices into the machine’.14 The schema does this by alerting us to words that bear upon others. So slot 5, with the most arrows, is the most important semantically.

This interest in conceptualising and representing semantics is, no doubt, influenced primarily by Masterman’s work on semantics dating back at least to her publication Semantic message detection for machine translation, using an interlingua (1961).15 John Sowa defines a semantic network thus: a ‘semantic network or net is a graphic notation for representing knowledge in patterns of interconnected nodes and arcs’.16 I believe this is what we can see in Fig. 4.

Masterman was a pioneer in developing the theory of semantic networks: hers was the first in fact to be called a semantic schema. The schema she developed, in her groundbreaking work on machine translation of languages, involved the description of concept types and formal patterns of relation.

Whilst such a schema works well for a machine to register connections based on pattern, later programmers of poetry have not taken up the schema, perhaps because it is rather unwieldy.

The purpose of the schema, the thesaurus and the template was to assist the non-poet to write a poem. Masterman did not over-rate the quality of the poems her program produced. To criticise the program from this point of view is to miss the point. Computerized Haiku is intended primarily as a learning tool for poets. That users during Cybernetic Serendipity suggested improvements and complained about the inadequacy of the available word choices, for Masterman proved the program worked.17

The use of an interactive mode in a public display at Cybernetic Serendipity marks one of the earliest instances of which I am aware. (There were already interactive computer programs. The first game was Spacewar, 1961. I do not know, however, if any were shown publicly.) It may be noted, the display of what was essentially a poetry-teaching tool in Cybernetic Serendipity is evidence of the curators’ willingness to look beyond conventional ideas of what should be shown in an art gallery. 18

Interactivity has perhaps become such an overused term and so familiar an experience that it easy to overlook its significance. It was, however, an important part of the premise of Computerized Haiku that it should exploit what, as I have mentioned, Mooers called the ’interactive typewriter’. Masterman, in her essay, explained that the option of batch processing, that is the complete automation of the program, had been considered and rejected.

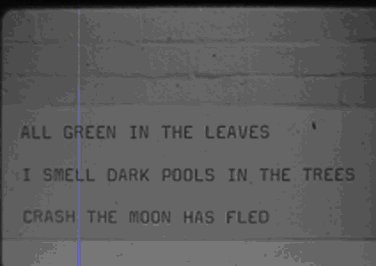

I have, however, pursued Masterman’s suggestion of a random haiku program. This program regularly violates all of the wise guidance provided to the human operator of the haiku program – or may make verses that seem to have contemporary relevance (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5. A haiku at www.in-vacua.com/cgi-bin/haiku.plMcKinnon-Wood with Gordon Pask were close associates and partners in the company System Research and had been involved in the development of cybernetic theory, particularly with their Conversation Theory (CT). That CT was part of the background of Computerized Haiku is indicated by this remark about Computerized Haiku that ‘the machine was to be used in conversational mode’.19

McKinnon-Wood also gave the final lecture given in a series at Cybernetic Serendipity. Entitled Talking to Computers, this dispels any doubt about the importance of CT to Computerized Haiku.

CT is an all-embracing attempt to comprehend how we come to understand through interaction with our environment. The theory has both a loose and a formal expression. In general terms, all learning situations may be conceived of as conversation. In strict conversation theory concepts such as ‘agreement’, and ‘consciousness’ are formalized processes of understanding.

CT is part of what is known as second-order cybernetics. This is distinguished from what is considered a more mechanistic earlier phase where systems are conceived as passive and the observer is more sharply distinguished from the observed. Second-order cybernetics is characterised by a recognition that systems themselves are agents in their own right and interact with us as agents (systems).

It is such considerations that form the theoretical underpinning of Computerized Haiku. It is this early venture into interactivity as informed by CT that may explain the work’s popularity at the time of its exhibition. However, it must be accepted that, despite the hopes of the programmers of Computerized Haiku, computers have not really caught on as a learning aid for poetry. (I can only speculate that those learning to write poetry prefer to dispense with mechanical assistance.)

The legacy

How, if at all, is Computerized Haiku to be remembered? To ask this is also to enquire into the reception of computerised literature in general. The history of computerised poetry and computerised literature, in fact, is yet to be written. There are several partial accounts, none of which, to be fair, claim to be complete. None that I know mentions Computerized Haiku.20

How has Computerized Haiku been received by those that do acknowledge it? Carole McCauley in her Computers and Creativity (1974) claims: ‘The haiku poems are … quite acceptable’.22 Ray Kurzweil’s The Age of Intelligent Machines (1990) reproduces several haiku without criticism.22 Margaret Boden’s The Creative Mind (1992), referring to Computerized Haiku, speaks of ‘the apparent success of this very early program’ .23 Funkhouser in Poetry, Digital Media and Cybertext (2003) finds, however, ‘these poems … reveal how generated poems can be monochromatic in structure when the syntax is unvarying and is predetermined’.24

Computerized Haiku remains significant as an early attempt to make computer poetry. It shows how cybernetic theory, programming languages and experiments in literature interacted to produce work that was new and exciting in its time. Computerized Haiku was according to Masterman, an ‘unexpected success’ of Cybernetic Serendipity.25

The other text pieces in the show do not seem to have fared much better than Computerized Haiku, although several of them are interesting and even ground-breaking, for example, Mendoza’s High Entropy Essays, or Balestrini’s Tape Mark 1. The best known is probably Edwin Morgan’s Computer’s first Christmas Card. Ironically, this is a simulated computer poem; it is not in fact a piece of computer writing.

Perhaps Stefan’s rather negative assessment, with which I began this exploration, is not wholly unfair and great works of computerised literature are yet to be made, despite the best attempts of ELIZA and Racter and their company.26

Nevertheless, it remains relatively early days for cybertext, and this area of literary production merits greater critical attention and further research. There are, no doubt, many more developments to be awaited in computerised poetry and cyber literature generally.

Conclusion

In conclusion, programming Computerized Haiku was an exercise in ‘archaeology’, but many other things as well. It was the first successful computer program I wrote. It was my first piece of work to be displayed on the web.

I have said that my initial interest was to look at a sort of ‘computational’ artwork, in its broadest sense: an artwork in a way divested of its material and historical ballast: something that aspired to the state of a sort of ‘pure instruction’ that could be translated between languages, constructed dis-assembled and remade. But this attempted act of retrieval has led me since to consider precisely all that cannot be regained and which constitutes the differences between there and then and here and now.

November 2004

Notes

Acknowledgements

I am particularly grateful to Jasia Reichardt, the curator of Cybernetic Serendipity, for her advice and assistance. I examined the archive at the Tate Gallery’s (London) Research Centre. This archive contains files of material from the ICA Gallery (where Cybernetic Serendipity was shown in 1968.) I wish to thank their staff for their help.I am grateful to Professor Brent MacGregor (Edinburgh College of Art) who has granted me permission to use two images (from the original ICA show) of Computerized Haiku in his possession.

Attempts were made, without success, to contact the Cambridge Language Research Unit where Margaret Masterman and Robin McKinnon-Wood, the creators of Computerized Haiku, held senior posts. However, the Unit is no longer active according to a Charity Commission report.

1. Stefans, B. K. (2003), Fashionable Noise. On Digital Poetics, Berkeley, Ca.: Atelos, p. 45.

2. Aceti, L. (2002) Getting Laid on the Procrustean Bed: Art Practice in the Digital World, One Man Versus One Pixel, <www.chart.ac.uk/chart2002/papers/aceti.html> (13 September 2004).

3. ‘The preservation of behaviours in the artists’ practice seems to be the main concern in contemporary digital art practice, where the presence of ‘software corporate powers’ are imposing a methodology upon art practice.’Cf. Aceti, L. (2002) Getting Laid on the Procrustean Bed: Art Practice in the Digital World, One Man Versus One Pixel, <www.chart.ac.uk/chart2002/papers/aceti.html> (13 September 2004).

4. Masterman, M. (1971), ‘Computerized haiku’, Cybernetics, art and ideas, Reichardt, J. (ed.), London: Studio Vista, pp. 175-184.

5. At Chelsea College of Art and Design, London, UK.

6. See Turing, A. (1936), On Computable Numbers, with an Application to the Entscheidungsproblem, www.abelard.org/turpap2/tp2-ie.asp (9 February 2003); Turing, A. (1950), Computing Machinery and Intelligence, <www.abelard.org/turpap/turpap.htm> (9 February 2003).

7. Reichardt, J. (ed.) (1968), Cybernetic Serendipity: the computer and the arts, a Studio International special issue. London: Studio International.

8. There is a list of Addresses of Major Contributors To Cybernetic Serendipity in the Tate archive, London. The contributors of text pieces, including Masterman and McKinnon-Wood, are listed under ‘graphics’ (the other categories are ‘music’, ‘film’ and ‘machines’.)

9. I owe this information to Jasia Reichardt, the curator of the show. Personal communication.

10. McKinnon-Wood, R. (1971), ‘Computer programming for literary laymen’, Cybernetics, art and ideas, Reichardt, J. (ed.), London : Studio Vista, 184-191, discusses some of these issues.

11. Sammet, J. E. (1969), quoted in Calvin N. Mooers Papers (CBI 81), Charles Babbage Institute, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis. <http://www.cbi.umn.edu/collections/inv/cbi00081.html> (5 September 2004).

12. See, for instance, Derrida’s discussion of its pre-eminence in Kant’s hierarchy of the arts. ‘The summit of the highest of the speaking arts is poetry’, says Derrida of Kant on poetry; Derrida, J. (1981), ‘Economimesis’, Diacritics, Vol. 11, p. 18.

13. It has wide and enduring usage. See Murray (1997) for an extended discussion of the many uses of substitution systems in literature.

14. Masterman, M. (1971), ‘Computerized haiku’, Cybernetics, art and ideas, Reichardt, J. (ed.), London: Studio Vista, p. 179.

15. Masterman, M. (1961), Semantic message detection for machine translation, using an interlingua, National Physical Laboratory, International Conference on Machine Translation of Languages and Applied Language Analysis, Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, London.

16. Sowa, J. F. (2002), Semantic Networks, <www.jfsowa.com/pubs/semnet.htm> (20 September 2004).

17. The contemporary descendant of Computerized Haiku is Ray Kurzweil’s The Cybernetic Poet, although much more complex.

18. Jasia Reichardt (1971) writes: “Thus Cybernetic Serendipity was not an art exhibition as such ... it was primarily a demonstration of contemporary ideas, acts and objects, linking cybernetics and the creative process” (p. 14).

19. From an article credited to the Cambridge Language Research Unit, but probably authored by McKinnon-Wood, or Margaret Masterman, or both; Cambridge Language Research Unit (1967), ‘Computerized Haiku’, Theoria to Theory, Vol. 1, Fourth Quarter, July, pp. 378-383.

20. For instance, there is Murray, J. H. (1997), Hamlet on the Holodeck. The Future of Narrative in Cyberspace, Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press; but this is about narrative. Aarseth, E.J. (1997), Cybertext. Perspectives on Ergodic Literature. Baltimore and London, The Johns Hopkins University Press, discusses prose as well as poetry. There is also Hartman, C. O. (1996) Virtual Muse: Experiments in Computer Poetry. University Press of New England, Hanover NH, a personal memoir of poetry and computers.

21. McCauley, C. S. (1974), Computers and Creativity, New York and Washington: Praeger, p.114.

22. Kurzweil, R. (1990), The Age of Intelligent Machines, Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, p. 370.

23. Boden, M. (1992), The Creative Mind, London: Abacus, p. 159.

24. Funkhouser, C. (2003), Poetry, Digital Media and Cybertext, <http://web.njit.edu/~cfunk/SP/hypertext/POETRYDIGITALMEDIACYBERTEXT2.doc> (10 July 2004).

25. Masterman, M. (1971), ‘Computerized haiku’, Cybernetics, art and ideas, Reichardt, J. (ed.), London: Studio Vista, p. 175.

26. ELIZA, Weizenbaum’s well-known non-directive therapist; see Weizenbaum, J. (1976), Computer Power and Human Reason, San Francisco: W. H. Freeman and Co.; Racter (1984), the reputed author of The Policeman's beard is half-constructed; illustrations by Joan Hall, introduction by William Chamberlain. New York: Warner Software/Warner Books.