Futures Past: Twenty Years of Arts Computing

|

|

Futures Past: Twenty Years of Arts Computing |

Colum Hourihane, Index of Christian Art, Princeton University

Sourcing the Index: Iconography and its Debt to Photography

Keywords: Index of Christian Art, Charles Rufus Morey, digitisation

There can be little doubt as to the enormous debt that the Index of Christian Art owes to photography. It is one that is rarely acknowledged and often taken for granted and yet it lies at the very core of the archive. This paper will attempt to redress that situation and will first look at the historical use of photographs in the archive before focusing on how that approach has changed over the last ten years.

Fig. 1. Charles Rufus Morey (1877-1955). Portrait by Ulyana Gumeniuk. Index of Christian Art, Princeton University.

Art history is a visual world in which surrogates of what are being studied are frequently used. These can range from black and white photographs to slides, transparencies or digital files. First hand experience of the works of art is rarely accomplished in the classroom although attempts are now being made to recreate virtual tours of both monuments and galleries, or individual works in which three-dimensional modelling is used. 1 No such developments existed at the start of the twentieth century when Charles Rufus Morey, art historian, diplomat, adventurer and chairman of the Department of Art and Archaeology (Fig. 1) visited the Bibliothèque Ducet in Paris to view a photographic archive. This archive was not arranged on the traditional basis of school or period or style but was accessed instead through iconography or subject matter; in which, for example, landscapes and portraits were separated and religious subjects were divided from the secular. 2 Upon his return to Princeton, inspired by such a structure, Morey began to arrange his collection of images – postcards, photographs, cuttings from newspapers etc. – into meaningful iconographic divisions and thus the Index of Christian Art was born. It is officially credited as having been founded in 1917. Iconographical classification, which is the strength of the Index, was initially driven by the availability of images. This must have led the first director and all subsequent ones up to 1955 (the year of Morey’s death) to claim at five-yearly intervals that they would have catalogued every known work of medieval art. Up until five years ago nearly every image in the Index was derived from publications. At the turn of the century there were few monographs on medieval art published every year and there were even fewer journals devoted to the subject. Nowadays, the number of monographs and journals on the period published in one week alone more than equals all such publications in a single year when the Index was founded.

The Index was the passive repository of whatever had been published – a source that was occasionally augmented by individual scholarly collections of images or rare expeditions to the sites themselves, although the distance from the United States to Europe and beyond in many cases must have proved to be a significant barrier. The Index was largely dependent on published images and as such was at the mercy of whatever scholars chose to study. Coverage could be sporadic and it was rare to find an entire manuscript reproduced or to get all the details of the façade of a cathedral illustrated so that the scholar in the Index could identify exactly what was represented. Even though the Index has always aimed for comprehensiveness it was dependent on what was reproduced. This has now changed and it is clear that the whole world of art history is well into the phase of documentation in which large and comprehensive image banks are at our disposal. The fact that the Index did not have complete coverage of every work seemed not to hinder scholarship too much.

The approach of the scholars in the Index was dependent on what they could see in these images. Magnification glasses were used extensively along with the descriptions of the works that accompanied such visual material, but the Index’s main contribution to scholarship was always an original evaluation of what was represented. The scholars were never dependent on what somebody else had said. Where works were not illustrated in publications, but where reference was made to them, then a ‘Temporary’ reference to such iconography was included and was not accompanied by any image in the photographic files. This was a less than satisfactory situation but one which attempted to be inclusive.

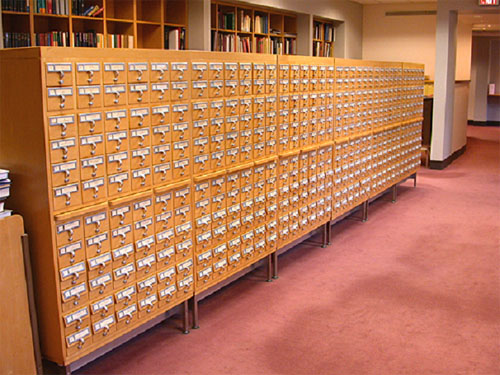

Fig. 2. General view of the Index files.

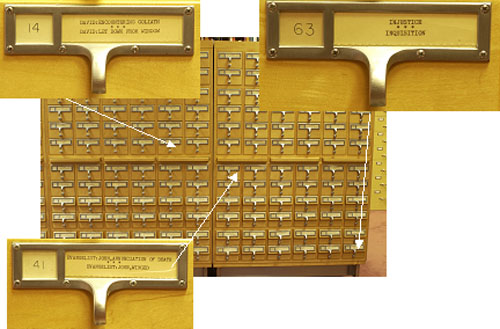

Accessing the images in the Index files was certainly easier than working with the text or iconographic files. Whereas each work was deconstructed textually in terms of its subject matter, and iconographic references were filed under their relevant subject terms (over twenty eight thousand of them now exist) the visual surrogates were kept together in one file and organised under the basis of medium and then location (Fig. 2). To see a folio from one manuscript the user simply had to go to the photographic files and look up under medium (manuscript, for example) and then location (Aachen, for example). It was possible then to examine what was filed under Aachen for all of the collections both private and institutional that had been recorded in the archive. However, to see the iconographical classification text cards for all the folios in that manuscript it was necessary to go to the relevant subject headings for the main theme of each folio which could of course start with ‘A’ for the subject term on the first folio and go to ‘Z’ for the subject matter on the second folio (Fig. 3). 3

Fig. 3. Index text files showing the possible breakdown in iconographical classification of a work of art.

From the researcher’s perspective it was clear that most followed a near standard approach in that once they had found the images required these were scattered on a research table to be looked at, compared and contrasted. In many ways this represented a manual version of the digital gallery format, or the lightbox facility now found in many computer applications.

Card Index

Once a scholar determined that an image should be included in the Index it was re-photographed and printed on standard size heavy-duty photographic paper, not once, but five times. The four duplicates were then passed on to the four manual copies of the Index, which were distributed in Europe and America. This procedure persisted up to the introduction of computers in 1991. At that stage, as with most archives, nobody knew exactly how many images or text cards were actually in the Index files. It is now estimated there is somewhere in the region of 950,000 file cards on which iconographic descriptions are recorded using twenty-eight thousand subject terms and these are accompanied by around 200,000 photographic cards. The quality of these photographs varies and obviously depends on how good the original was. The quality of photographic prints varied enormously at the start of the last century. All of the images are in black and white as that was the prevalent medium when the Index was being developed. It was also felt by Morey, in his attempts to be as objective as possible, that black and white was the best means to do this. This policy remained unchanged until the late 1990s. Coloration and its significance were described, if relevant, in the textual descriptions but this was not paralleled in the images. The objectivity of these images depended on who took the original photographs and the aims that they fulfilled, but that was a remit which was certainly outside the Index’s control. These images represented for Morey the most objective visual response that he could offer to the user. His use of this medium was typical of his stance on the entire process of iconographic analysis and it is my belief that the Index contributed extensively to the formulation of Panofsky’s methodology of subject analysis, which was very much based on the system that had been employed in the Index for some twenty years before his work was published. 4The Index has always attempted to improve on its photographic holdings. When a better example of an image already existing in the Index was discovered it was re-photographed and added to the files as indeed were any new details of the larger works. Nevertheless, the primary function of these images was always to offer a visual parallel to the description made by the scholar. The images were meant to provide the user with a visual parallel to the textual description, which was the original contribution of the archive to scholarship. Without such an analysis the photographic files were simply that – a large archive of images. Where objectivity was concerned it has to be said that the iconographic interpretation, with its subjective input from the scholar, does make it an unequal situation. It is true that greater scholarship was required in the iconographic analysis than in the generation of images. The images were entirely outside the control of the archive – the Index offered a synthesis of such reproductions. The development and application of iconographic standards however was created within the Index and greater input was given to their development to ensure consistency. Whereas objectivity in the creation of images was determined by external sources over which the scholar had little control other than selecting, the Index was entirely responsible for the creation of textual standards. 5

Computerisation

For over seventy-five years the Index’s collecting policy was largely driven by what was available photographically – a source that was often unacknowledged and not given its due credit. The major break in this policy came with the advent of computerisation. Although late in impacting on the Index this led to a major change in the use of images and text. Computerisation came to the Index in 1991 when a modified version of a bibliographic standard was first used in the archive. 6 From the outset the policy was to maintain the existing text and image files but also to add to them. This cautious policy was a feature of the early eighties in that the use of computers was in many ways seen as an experimental phase, which had yet to show its value. All of the existing data elements that could be found on the paper files were reproduced electronically although some new fields were also added. Typical of such additions were fields such as ‘Style’ and ‘School’ which were anachronistic to the founders whose aim was to present as objective and non-interventionist a stance to the data as was possible. These new fields in many ways reflected art history in the late 1980s-early 1990s and also catered for a new audience that needed to have such standards included. Like most archives undergoing computerisation the Index was initially content to focus on the textual record and this was to last for many years without any image component. It was felt that the inclusion of a bibliographic reference to a printed image in the text records was satisfactory and that it would not be too much of a problem for the user to go to the library to get the bibliographic reference to see the actual image. That of course assumed that each user had a fully-stocked library that would carry the same range of material that the Index had developed over more than ninety years. Image digitisation was begun at the Index in 1998 and heralded a series of major problems regarding the copyright and ownership of the photographs. Whereas the iconographical analysis in the form of the text records was entirely the property of the Index the rights to the images lay outside of the archive.

User needs demanded that an electronic image accompany the computerised text record and it was realised that the policy regarding images would have to change. The archive was still dependent on the image for generating new material to add to the existing resources. Upon closer inspection it was clear that many of the images that had been collected over the last eighty-five years were now out of copyright and could be offered to users of the database. When we came to digitising the images we were able for the first time in the history of the archive to have control over image quality and could vastly improve the archive. Objectivity in this instance was led by our efforts to get the best out of the images and this was achieved by applying international standards in image manipulation. We followed accepted conventions for file size, type, naming etc. Digitisation gave control of these images to the archive for the first time and not just in terms of copyright. Of the 120,000 images that are now available on the Index website 7 and which have been digitised within the last six years, approximately 40,000 have been culled from the existing photographic files. These have been classed as ‘Public images’ in the database and are accompanied by several thousand for which we do not have copyright and which are ‘Restricted’ to the Princeton campus. Needless to say our policy is to add to the images that we can offer to the public and this has brought about a number of significant changes in our image acquisition policy which have also impacted on the whole direction in which the Index is moving.New Directions

The Index continues to draw extensively from published material and where possible permission is actively sought to make the images of such work available on its website. Such images are no longer added to the existing photographic files but are now digitised only. There have been a number of other significant and recent changes in the image policy of the Index. The Index has started to work collaboratively with a number of institutions who have either image or object collections which are not digitised. The Index has the resources to digitise such archives, make them available on its own website and in turn return both text and image records to the owner institutions for their own use. This continues the role of the Index as a synthesis for such material but now it is for previously unpublished material. In the last five years the Index has worked with public and private image collections such as those of Erica Cruikshank Dodd, Peter Harbison, Tuck Langland, James Mills, Gustav Kuhnel, James Austin, The American Research Center in Egypt, Dumbarton Oaks, and Mat Immerzeel to name but a few. These collections are digitised and then added to the Index once catalogued.Paralleling this is an active policy to photograph directly from the works themselves and as such to get copyright and control over what is photographed and how this is done, (Figs. 5, 6) This has again led to a number of collaborative and independently-funded projects to photograph and iconographically classify collections such as the Morgan Library, New York, Firestone Library Collection, Newark Museum, the Free Library Philadelphia, The Paul Van Moorsel Centre for Christian Art and Culture, University of Leiden (Fig. 4) and so forth. The Index photographer is able to visit such collections and work directly with the curators in acquiring images for the Index. Another strand to this acquisition policy is the development of a series of studentships in Israel which enable students to visit works in the field, photograph them and then transfer the images to Princeton for inclusion in the database (Fig. 5).

Fig. 4. Wall painting from Deir-al Surian, Egypt. Photo: Paul Van Moorsel Center in the University of Leiden.

Fig. 5. Churches in Shivta, Israel.

Much of this material, whether it is in the Morgan Library or in the Negev Desert in Israel has never been photographed or iconographically catalogued and as such it has brought the Index into the role of original publisher. The Index has had to adapt and change with the development of new technologies and approaches.

The new policies include the following:

- The Index now has an active policy of photographing from original works of art and has extended its available resources.

- The Index has now entered into the role of original publisher and includes visual material that has never before been reproduced.

- The Index has entered into the role of collaborator with a number of institutions.

- The Index is now able to photograph entire collections.

- The Index now uses digital files only (except in the case of the Morgan Library which still continues to be shot in 35mm slide film alongside the digital format).

- The Index no longer restricts itself to black and white images and has used colour extensively especially when photographing from original works of art.

All of these drastic changes which have been developed in the Index in the last six years have changed the role of the photograph in the archive but have not lessened our dependency on it as a source for new material. Now however, thanks to collaboration we are at liberty to examine the original works themselves and there are very few ‘Temporary’ files being added. Thanks to image digitisation the Index now offers unparalleled detail in high-resolution large format files. Scholars in the archive are now able to read intricate lettering on their computer screens and to see the most minute features in these images. Computers have replaced the magnifying glass in terms of examining the visual material. In many ways we have now come full circle and instead of being totally dependent on images we can now have an active input into our acquisition policy and an element of control that the Index never before had.

November 2004

Notes1 An example of this is the unique recreation of the Dunhuang Caves in the Gobi Desert now available through the Mellon Foundation sponsored ArtStor site http://test.artstor.org (20 September 2004).

2 See Hourihane, C. (2002), ‘ “They Stand on His Shoulder”; Morey, Iconography, and the Index of Christian Art,' Insights and Interpretations, Studies in Celebration of the Eighty-Fifth Anniversary of the Index of Christian Art, Hourihane, C. (ed.), Princeton, pp. 3-16.

3 The best description of the structure of the Index is found in a handbook by Woodruff, H. (1942), The Index of Christian Art at Princeton University; with a foreword by Charles Rufus Morey, Princeton), and the more recent article by Ragusa, I. (1998), ‘Observations on the History of the Index : In two parts', Visual Resources, 13:3-4, pp. 215-52.

4 See Hourihane, C. (2002), op.cit.

5 This was particularly important as other archives were using the same standards. The Morgan Library in New York, for example, used the Index standards in cataloguing the iconography of their manuscript holdings. The 1942 publication by Helen Woodruff (cf. note 3) encouraged others to follow these standards.

6 The computerisation of the Index and the software employed are discussed on the home page of the archive at www.ica.princeton.edu (20 September 2004).

7 The Index of Christian Art offers its resources on the Internet using a subscription scheme, details of which are available on the home page at www.ica.princeton.edu (20 September 2004). It is now the largest resource for the medievalist on the World Wide Web with many hundreds of thousands of records available.