Theory and Practice

|

|

Theory and Practice |

Ann-Sophie Lehmann, University of Utrecht, The Netherlands

Invisible Work. The Representation of Artistic Practice in Digital Visual Culture

The construction of digital artworks demands a wide range of expertise. Conception, production and technology are closely intertwined; existing technologies have to be adapted to new artistic concepts, and new technologies inspire and create new meanings, iconologies and contexts. In order to realise a work of art – be it an installation in a gallery or museum, or an online work – an artist has to be engineer, programmer, graphic designer, and hardware constructor all at once, or has to have access to others who are able to shape technologies and materials as required. In the case of Daniel Rozin’s Wooden Mirror (1999) for example – a work that produces the reflection of any person facing it by slightly shifting the polished wooden blocks of which the surface of the mirror is constructed – the cameras, motion sensors, software and wooden blocks were all custom made. 1 In a sense, the construction of such complex, interactive works returns the digital-media artist to an era before the pre-manufacturing of artist’s supplies. Before the invention of metal paint tubes in the nineteenth century, before standard-sized canvasses or marble blocks were available, artists depended on custom-made materials, and workshops with trained assistants, just as the media artist today might depend on programmers and engineers to provide custom-built technology. Even when artist and programmer are the same person, for example the net.art practitioners Jodi (http://text.jodi.org/) or Olia Lialina (www.artlebedev.ru/svalka/olialia/), the procedures of art making are no less intricate or complex.

Thinking about the versatile practice of new media artists leads to the question of what this practice might look like. One way to find out is by studio visits or reading and listening to interviews with artists.2 Another way is to look at the ways media artists represent their own practice. Throughout history, artists have always taken care to display and advertise their art-making skills in genres specifically created for this purpose. Some of the first representations of artists at work may be found in illuminated manuscripts and in the early Renaissance the representation of St. Luke painting the Madonna became a way to depict artistic practice and skill. Within a century the Christian iconography of the painting apostle evolved into the independent self-portrait at the easel, and the atelier scene. Both genres were still widely popular in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, adapting their specific iconography to changing artistic practice or new technologies. Considering today’s multi-faceted media artist as described above, one could expect a continuation of the iconography of ‘the artist at work’ into the digital age. But is practice represented in the age of digital art? Do artists draw attention to the processes and procedures of their work? The question about a contemporary iconography of the representation of practice raises more general questions about the spatial, material and theoretical aspects of contemporary artistic practice: what kind of materials and tools are used to construct media art and how do artists employ these tools and materials in their creative spaces? How are these creative spaces defined and located, and can they and the creative processes within be visualised?

My first tentative answer to these questions is negative – digital modes of production do not appear to favour the representation of the artist at work because the very process of making is rendered invisible by the medium itself. However, this hypothesis must be tested. In order to determine whether or not representation of practice is absent in the creation of digital art, this article will reflect on four aspects relevant to the question at stake. Beginning with a short analysis of the meaning of representations of artistic practice in the pre-digital era, a more thorough analysis of the location and designation of creative spaces in the digital era will follow. The representation of digital tools and materials used by media artists will then be focused on, incorporating a brief comparison with the representation of practice in a field related to media art – computer graphics and animation.

The Representation of Artistic Practice and Creative Spaces in the Pre-Digital Era

Fig. 1. Sofonisba Anguissola, Self-portrait at the Easel, 1556, Muzeum-Zamek, Lańcut, Poland. Reproduced with kind permission.

In the pre-photographic era artistic practice – especially painterly practice – was represented in genres displaying artists working at their easels in their workshops (Fig. 1). Needless to say, these scenes are not objective representations of generic practices, but carefully staged scenes designed to entice the viewer with the display of artistic skill.3 At the same time, these scenes served to invest an artist’s working space with near magical qualities. The careful presentation of the ‘artist at work’ with brushes and paints (or their equivalents), in a studio space adorned with models, preliminary sketches and unfinished works, evoked the aura of creation. The images suggested that these spaces not only contained the materials and tools necessary to make works of art, but also housed the inspiration and genius necessary to conceive them. Furthermore, the images enhanced the mystery of artistic creation through an interesting pictorial paradox. On one hand, atelier scenes allow us to witness the act of creating a painting, seemingly instructing the viewer in the actual making of pictorial illusions. Yet while we appear to observe the processes of painting – a brushstroke being made or paint being mixed – the acts displayed before our eyes could never be copied purely based on this visual information. Therefore the visual representation of making art does not give away the artist’s secret of how to make art. Consequently, the visualised process of creation becomes all the more mysterious.

Later, photography and film would replace the handmade depiction of the skilful self at work. Here, the creative process was made visible to the public, seemingly unravelling the mystery of art making, while heightening the magical element of creation. To this day, the studio space lends itself to the idealisation and mystification of practice, and the physical presence of the atelier is associated with the imaginary presence of the creative process. Even with the artist dead and gone, the deserted studio continues to breathe the aura of creation and is treated as a shrine, with the material remains as relics. The recent transfer of Francis Bacon’s entire studio contents from London to Dublin, and the exhibition of Perry Ogden’s beautiful photographs of the chaotic workshop, as works of art in their own right, is a perfect example of the cultural value attached to the traditional creative environment. 4

In conclusion it may be stated that until very recently, the representation of practice was closely tied to the aura of material practice. This ‘materialist’ notion is incorporated in the very naming of the artist’s space: the term atelier derives from the Latin atele, which referred to the wooden shavings in a carpenter’s workshop.

The Designation and Location of Creative Spaces in the Digital Era

New media have led to the formation of new creative spaces; spaces that seem to have caused a dislocation of the materiality of the traditional working space. In order to locate digital artistic practice and its representation, this section will attempt to trace and outline the physical, metaphorical and theoretical appearances of these new spaces.

Beginning with the designation of the new spaces, it is remarkable that in new media art practice, a working space is frequently referred to as a laboratory rather than a studio or atelier. If McLuhan’s concept of hot and cool media is applied to spaces, the laboratory would inevitably turn out as the ‘cooler’ space. Often abbreviated as media lab or design lab, the new working space is a sharp contrast to the traditional concept of the studio. Obviously, this shift owes much to the essential role of technology in new media art. Also the notion of creation associated with the traditional studio might be less appealing than the notion of experiment associated with the laboratory. Yet the laboratory, just like the studio, carries its own traditional set of connotations which are deemed highly problematic by some scholars. In science and technology studies – most prominently by Bruno Latour – the laboratory has been criticised as the ultimate black box. Latour characterised the laboratory as a place where experiment and invention are kept from public view, and only finite results are allowed to emerge after having been carefully wrapped in impenetrable layers of scientific reasoning.5 Although the artist’s laboratory has come to signify the cross-disciplinary link between art and science and could therefore symbolise a partial opening of the black box; the production and making of the art still seems to be hidden behind the walls of the lab. Consequently, there is no equivalent to the traditional depiction of the atelier described above, no laboratory-iconography representing the work that goes on inside.

This obscuring of creative practice is matched by an apparent reluctance to describe the technological processes behind digital artworks with words.

In recent overviews of new media art, very little attention is paid to the actual production of the artworks discussed.6 For example, although net.art plays with digital technologies or addresses their impact on art, society and politics, the actual technologies and procedures behind the individual artworks remain obscure. Artists simply ‘draw links between sites’; ‘build online artworks’; or present ‘a sophisticated piece of programming’.7 In the few instances where artists refer to their own practice, we get a notion of their presence behind the computer, yet we have no idea what they actually do with the computer. In a 1997 interview net.art pioneer Vuk Cosic describes how he has neighbouring studios with Heath Bunting, Alexei Shulgin and Olia Lialina, emulating the studio set-up of Picasso and Braque in early twentieth-century Paris: ‘We steal a lot from each other, in the sense that we take some parts of codes, we admire each other’s tricks’. The Belgian duo Jodi wrote in the early 1990s: ‘it is obvious that our work fights against high tech’.8 The drawing and building, the comparison with Braque and Picasso, the fight against ‘high-tech’ draws on traditional terminology and metaphors. The vocabulary for the description of the technological aspects of new media art practice on the other hand is limited. So how do we imagine the code-tricks Cosic mentions? How do we differentiate between high- and low-tech if technology is neither a verbal nor visual issue in the self-reflection of practice, and in the critical analysis and public presentation of art works? Maybe technology is still considered dull to the wider public? The result being that ‘techno-talk’ is consequently kept to a relatively small, artistic community that possesses sufficient technological understanding.

It is interesting to note that the notion of the laboratory with its metaphorical connotations of secrecy and highly specialised technological processes, in combination with the textual silence surrounding these processes, contradicts a vital ideal proclaimed by new media culture and theory. This ideal envisages new media as open-source, enabling technologies, which (ideally) facilitate and inspire the participatory production of culture.9 This contradiction between the ‘black boxing’ of artistic practice and the ideal of a participatory culture might be owing to the mechanisms of the art market – above all the demand for originality – to which eventually even the most non-conformist artist may succumb. In order to solve this conflict, open the ‘black box of practice’ and represent the new media artist at work, a means to facilitate the description and visualisation of the technologies used in art practice must be found.

In addition to the symbolic and physical shift of the site of production from open studio to closed laboratory; new media have had a more profound impact on the notion of space. On a theoretical level, new media have divided the notion of space into metaphorical and/or virtual spaces on one hand and actual, physical spaces on the other.10 The inherent dichotomy of real and non-real spaces, as argued by new media theorists such as N Katherine Hayles and Mark Poster, should be discarded in favour of a model they base upon Michel Foucault’s concept of a heterotopia. This model suggests that through new media, virtual and physical spaces intersect each other simultaneously, continuously creating new spaces, all of which co-exist in a non-hierarchical structure.11 New media artworks are a perfect illustration of these new spatial heterotopias. In new media art works – as George Legrady, theorist and practitioner in the field of digital media, pointed out as early as 1999 – metaphorical and virtual spaces always intersect with physical spaces: ‘In the process of interacting with the digital world, we can consider real space as the site where our bodies come into contact with the technological devices by which we experience virtual space’.12 Legrady points out the embodied visual or sensual experience of the viewer when looking at new media art in physical spaces like museums but also on computer screens. The art works themselves however are, as he emphasises, immaterial: ’Artists who create in digital media can produce works that do not require embodiment in a physical object. These works are free from the constraints of materiality as they exist as numeric data […]’.13 Legrady argues that the artwork, ‘free from the constraints of materiality’ arrives at an intersection of the virtual and the real when it is being viewed and experienced. In his argument, Legrady puts the immateriality of the artwork first, but what about the other end of the process, the initial making of the immaterial art work? Before becoming immaterial there must have been a form of interaction between the maker and the digital building-blocks of the artwork under construction, equally embodied as the experience of the viewer of the finished piece. It follows that the artwork is only immaterial between making and viewing while the processes of production and perception imply a partial materiality. Just as the act of perceiving is bound to a physical location, so the physical interaction between the artwork and its maker must have a location of some sort, somewhere within the Heterotopia of intersecting virtual and physical spaces.

Where then could the creative space of the new media artist be located? An artist of the Amsterdam KKEP collective (www.kkep.com) told me about the process of making a collaborative piece. While she was in Amsterdam and her collaborator in New York, they would work in the ‘natural’ shifts dictated by the time difference, and send their work back and forth to one another via the Internet. Not only did they get twice as much work done as they would have in the same time zone, they also profited from the creative input of the different environments they lived in. I interviewed Joanna Griffin, who works with the visualisation of satellite data, at the Utrecht Impakt Festival 2004 (www.impakt.nl), about her ideal working space. She described it as ‘a place where I can plug in my computer and make coffee’. In both cases, the physical location of the artist overlaps with the creative space to a certain extent, yet the latter is obviously much more than somewhere to plug in the computer and make coffee. The creative space is much more difficult to mark out. Can it be found at the desk, in front of the computer, or rather at the intersection of the physical and the machine world, the ‘human computer interface’? Is it the computer itself, like the practice of case-modding suggests, creating visual spectacle by turning the outside of the computer into a personalised artefact; is it inside the computer where software programs like Photoshop, Maya or Paint mimic the artist’s studio with its traditional tools and materials, or is it in the virtual space beyond the machine? Or is it in all these places at the same time: an oscillating creative space; an artistic new media heterotopia?

While the last option, the oscillating creative space, is the most likely answer, this space is at the same time the least tangible and concrete. More insight into the possible structure of this creative working space may be gained from the field of computer science. In order to design collaborative virtual environments, much research into the spatial experience of users who engage and work with digital technologies has been carried out. A basic outcome of this research has been to state the existence of multiple, simultaneous, hybrid spaces in which users move about. Letting go of the spatial dichotomy between (pure) physical and virtual spaces provides a parallel with the theory of the digital heterotopia as described by Poster. Computer science however, needs to move beyond theoretical concepts in order to translate the spatial hybrids back into concrete designs. During this process, the new spatial conditions (which, as illustrated above, tend to evade exact positioning) need to be redefined outside the restrictive terminology of geographical location. In order to do so, Paul Dourish, Professor of Computer Science at the University of California, Irvine, introduced the distinction between space and place in his call for a social design for collaborative virtual environments. This concept, borrowed from the social sciences, allows for a non-geographical definition of the new spatial situation because it adds yet another layer to the hybridisation of digital and physical space: the flexible meaning of spaces in their form as place. According to Dourish ‘spaces are part of the material out of which places can be built. Dealing with physical structure, topology, orientation and connectedness, spaces offer opportunities and constraints. Places, on the other hand, reflect cultural and social understandings. Places can also have temporal properties; the same space can be different places at different times.’14

Dourish’s differentiation between space and place also helps to identify the creative working space of the artist: it is a socially- and culturally-shaped place, created from the hybrid fabric of virtual and physical spaces. On a conceptual level, this definition brings us closer to the whereabouts of the artist at work in the digital domain. But it still does not help to visualise this place. On the contrary, the oscillating, creative virtual and physical space/place seems to resist representation even more than it evades verbal description. Perhaps it is best to conclude that the creative spaces of new media artists cannot be represented, simply because there is no fixed space left to depict.

The Visibility of Digital Tools and Materials

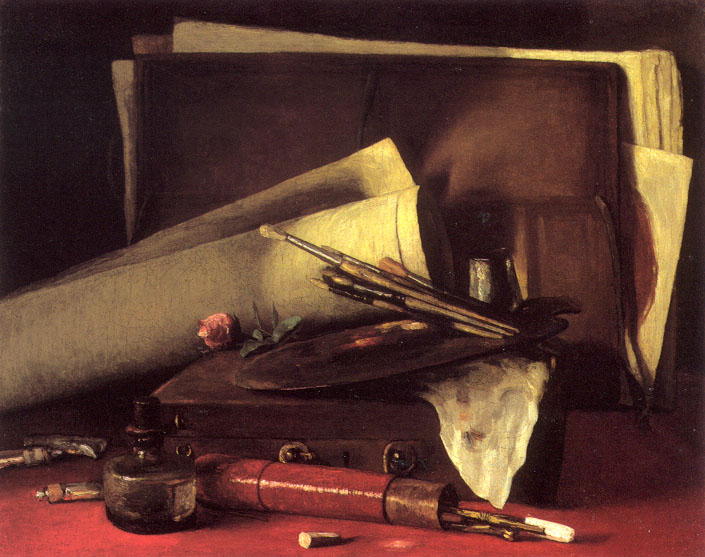

While the creative space seems to defy representation, there are other ingredients of the art-making process which do not. These are the tools and materials of the new media artist in or at the computer. Just like the creative space, tools oscillate between a physical and virtual presence, because the keyboard, mouse, pen – or in the case of touch-screens the hand itself – are tangible devices translating movement into digital action on the screen. Most of the time, the virtual part of the tool is represented by an icon referring to a familiar device of non-digital origin, like the brush, pen, spray-can, magic wand etc.15 The physical tool can operate a variety of different, even opposing, virtual tools. For example, the mouse controls the eraser as well as the clowning device in a paint program. Yet in spite of their hybrid structure and seemingly simplified functions, the tools demand a user just as skilled and sensitive to their creative potential as do ‘traditional’ tools, as Malcolm McCollough pointed out in his important study Abstracting Craft.16 Digital materials are more evasive than tools because they have no physical component but are entirely virtual. Yet even in the virtual domain, they oscillate between two shapes. On the surface, they resemble artistic material of the physical domain (images, paint, brushstrokes, colour etc.). On a different level they are software, part of software, or in their purest form, code. A simple example is the HTML code attached to each color. The fact that digital tools and materials are ultimately represented in such forms could turn them into an interesting element of the (so far) hypothetical representations of the new media artist at work. However, where the brushes and palettes, chisels and rulers, marble slabs and paint tubes, paper and charcoal of pre-digital artists figure prominently in the (self)-portraits discussed above, there is no comparable elevation of their digital counterparts discernable yet. It is indeed hard to imagine a depiction of a mouse or a brush icon as lovingly and romantically as, for example, the tools in François Bonvin’s Attributes of Painting (late nineteenth century, Barber Institute of Art, Birmingham, Fig. 2) where palette and brushes symbolise the creative process. Taking into account McCollough’s call for a digital craft, it could merely be a question of time until digital tools are used in representations to evoke the magical aura of artistic creation. So far however, the familiar metaphors dominate.

Fig. 2. François Bonvin, Attributes of Painting, late 19th Century, Barber Institute of Fine Arts, Birmingham. Reproduced with kind permission.

In this context, we may observe that digital tools and materials have not shed the iconic or symbolic bond with their precursors, as the media theorem of the ‘horseless carriage’ syndrome would have it. On the contrary, the current development of design software strives for an ever more perfect imitation of the materiality and tangibility of traditional artistic tools. The desire for a reconciliation of the senses of vision and touch, separated by the digitalisation of creative processes, is present in the amazingly precise imitation of artistic materials, from different sorts of digital canvas to virtual oil-paint that actually needs to dry, to applications simulating the direct/immediate touch of virtual objects and tools in 3D environments. These developments in the design sector push towards the frontier of what David Jay Bolter and Richard Grusin have called the myth of ‘transparent immediacy’.17 In this ideal and never completely realisable state the user could become ignorant of all traces of mediation and ‘handle’ digital material and tools directly. One might ask if the continuous effort to recreate traditional materiality in virtual environments does not restrain the development of tools and materials of an essentially digital nature, without precursors in the non-digital domain. So far, the metaphor of the painter’s, sculptor’s or architect’s tools and materials, proves to be a lot tougher than the creative space where the tools and materials are handled, which easily gave away to new forms of hybridisation.

It is interesting to see how digital tools, now they have become tangible and have reappropriated, as it were, the aura of traditional creation, also become attractive for representation. I will illustrate this with two examples; one is an educational application, the other an artwork (Figs. 3 and 4).

Fig. 3. Boy working with the I/O brush, http://web.media.mit.edu/~kimiko/iobrush/

The I/O brush is a multimedia tool for children, developed by researchers in the MIT Media Lab. It is an oversized brush with a wooden handle and bristles that incorporates a small camera. With the brush, the children are able to film a certain structure or surface and then paint with this image on a digital canvas (the application is reminiscent of the ‘image-hose’ in paint programs). The central notion is the effortless incorporation of real-world materials into digital art projects. In the articles describing the I/O brush and on the MIT website, photographs and short films show the fun and ease with which the children use the ingenious combination of digital technology and tangible tool. Watching the little artists at work, the viewer is immediately convinced of the success of the brush.18

Fig. 4. Daniel Rozin, Easel, http://smoothware.com/danny/neweasel.html

Daniel Rozin’s art project Easel (1998) functions in a comparable way. A computer screen is set on a painter’s easel so that it appears as a traditional canvas. On the ‘canvas’ gallery visitors may combine and modify live video images and material from the Internet with a digital device mimicking a brush. Rozin describes his work as ‘a group made of two pieces that build on the concept of painting with video. The pieces in this group are truly interactive as the visitors are encouraged not only to incorporate their image into the piece but to actively paint and change the whole appearance of the piece, becoming the artists themselves’.19 It is essential to this concept that Rozin’s artwork is neither only the easel and digital canvas, nor the various works the eventual users will create. The work of art is the sum of the whole interactive process of creating images.

In both cases, the focus is on art being made. Yet, the ‘showing making’ does not represent the creators of the application or artwork, it represents those who interact with the finished product.20 So we become aware of is the intricacy of the technology, which has been made to disappear behind the metaphor of painting, enabling others to use it within the familiar frame of traditional artistic practice. The artists/technologists remain invisible.

The Making-Of in Computer Graphics and Animation

So far, the search for the representation of artistic practice in the digital domain has been rather unsuccessful. Yet there is an area of digital image making where processes of production are almost excessively represented: the field of computer graphics and computer animation. Here, ‘showing making’ has even been defined as a separate genre, the ‘making-of’. As a genre the ‘making-of’ is much older than computer graphics, but through the use of digital image manipulation in film it has gained tremendously in popularity. This is owing to the new form of image creation. Artificially-created photorealistic images captivate viewers because they have no indexical equivalent in the real world. Things, people, places that never existed, or do not exist anymore (e.g. dinosaurs), and events that never took place or are impossible to film in the real world may be visualised with the help of a computer.21 A way to appeal to the fascination and apprehension caused by CGI is to show how these images were generated. This can be for explanatory as well as commercial reasons. In a traditional ‘making-of’ the viewer gets a peek ‘behind the scenes‘, listens to the director’s erudite commentary, watches actors being interviewed on the set and witnesses hilarious ‘bloopers’. The iconography of the ‘making-of’ computer-animated scenes looks rather different. It is much more static. Most of the time we see animators or technicians sitting in front of computers, displaying skilful manipulation of tools and immaterial materials while the images they create come into being on a screen. Glancing over the shoulder of computer wizards, we might witness the different stages of a spectacular stunt, like the ‘bullet time’ effect in the Matrix trilogy (Wachowsky Brothers 1999-2002) or the building of an underwater anemone in Finding Nemo (Stanton and Unkrich 2003) on its way to photorealism, from wire-frame animation to a fully-coloured and shaded sequence. The formal set up of these ‘making-ofs’ bears a close resemblance to the iconography of the atelier-scenes discussed above. (Fig.5) The genre also answers to the same visual paradox. Practice is displayed without giving away the secret of the actual ‘how to’. Showing the computer animator at the screen does not deconstruct visual illusion. If this were the case, we would probably not enjoy watching ‘making-ofs’. Yet, regardless of their promise to reveal the making of illusion, the genre does not destroy but rather enhances the pleasure of looking.22 Part of this pleasure is achieved because we learn about the amount of work and skill invested in the creation of illusionist imagery. This knowledge causes the viewer to admire the dexterity and competence of the maker(s), and the stimulation of awe is also of economic value.

Fig. 5. Computer Artist at Work and Anguissola’s Self-portrait (see Fig. 1).

Commercially speaking, the ‘making-of’ is a way to display the power to shape technology (‘only we can create these images’).

Although a fixed mode to represent practice does exist, new media artists generally do not use the ‘making-of’ to reflect on their practice. This might be owing to a number of reasons, such as the commercial aspect and the predetermined appearance of the genre. But predominantly, an artist might not employ the visual strategies of the ‘making-of’ because it is so closely tied to the creation of photorealist or at least representational imagery. This is also the reason why the ‘making-of’ can seamlessly tie back to the visual vocabulary of the painter in front of the easel. Mimicking reality and creating visual illusion profits by showing or showing off practice, be it in the sixteenth or in the twentieth century. Yet today’s new media creative practices encompass infinitely more strategies than the representation of realistic computer generated-imagery. Artists who operate within this set of paradigms seem to prefer not to represent themselves (at work) at all.The Artist at Work

To summarise, the process of artistic practice seems to be rendered invisible by a variety of factors: the metaphor of the laboratory; the difficulties in describing and visualising the procedures of data programming; the hybridisation of creative space; and the multiplicity of artistic practice within this space. Practice itself does become visible, but only in certain instances, dissociated from the artist. It appears in the digital tools mimicking analogue predecessors, in digital materials like software and data, or in interactive art-works engaging the viewer/user. However,the embodied representation of the artist at work only resurfaces when creative practice remediates traditional modes of art-making, like the affirmative creation of realities in computer graphics and animation.

Two conclusions are possible. Either the representation of artists at work has become obsolete in new media art practice and the mystification of artistic creation has finally been discarded, or the representation of practice has become just as hybridised as the space in which it takes place. Most likely, creative practice in the digital domain is still in search of representation, and as it is a self-reflective genre, it might take some time to develop modes to do resolve this issue.

An example of how practice might present itself is the Life-Sharing project of the net.artist collective 0100101110101101.org. It ran from 2000-2003 and enabled users to directly access the artists’ computers. Based on the assumption that people are their computers 01.org not only wanted to lay bare their own artistic practice but also their everyday life practice by allowing users to witness, copy, interfere, and ultimately become their practice. In an interview with Matthew Fuller, the group stated that Life-Sharing was not concerned with representation. Yet on their website the project is described as ‘a real-time digital self-portrait’. In addition, the title of the interview ‘Data Nudism’ and other articles titled ‘Portrait of the Artist as Hard Disk’ or ’The Self on the Screen‘ clearly allude to representations of the making and maker of art-works.23 Yet it is indeed difficult to grasp the exact shape of this representation. In Life-Sharing the artists become perceptible in the form of data, when the user/viewer chooses to interact with these data. Rather than leaving representation behind altogether, it seems that showing the act of making art has been shifted toward the domain of the user. Because it depends on the process of sharing, the artwork needs the user to come into being. As a result, it has simultaneously become the site of its own ‘showing making’, leaving the physical presence of the artist behind.

Notes

1. The work is discussed in Bolter, D.J. and Gromala, D., (2003), Windows and Mirrors. Interaction Design, Digital Art, and the Myth of Transparency, Cambridge Mass.: MIT Press.

2. The Tate Modern for instance has collected over many interviews with artists, see www.tate.org.uk.

3. For recent discussions of the relevance of these genres in different periods see for example Wetering, E. van de (1997), Rembrandt, The Painter at Work, Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, and Mongi-Vollmer, E. (2004), Das Atelier des Malers. Die Diskurse eines Raumes in der zweiten Hälfte des 19. Jahrhunderts, Berlin: Lukas Verlag. For a recent bibliography see M. Haveman, M., Lehmann, A., Overbeek, A. (2006), Ateliergeheimen, Zutphen/Amsterdam: Kunst&Schrijven.

4. see www.hughlane.ie/fb_studio/ (20-04-1006).

5. Latour, B. (1987), Science in Action: How to Follow Scientists and Engineers through Society, Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

6. Stallabrass, J. (2003), Internet Art; The Online Clash of Culture and Commerce, London: Tate Publishing; Greene, R. (2004), Internet Art, London: Thames and Hudson; Paul, C. (2003), Digital Art, London: Thames and Hudson; Wilson, S. (2002), Information Arts: A Survey of Art and Research at the Intersection of Art, Science and Technology, Cambridge Mass.: Harvard University Press.

7. Stallabrass, J. (2003), Internet Art, p. 27, 29, 34.

8. Stallabrass, J. (2003), Internet Art, p. 38. An exception is Olia Lialina’s article ‘A Vernacular Web. The Indigenous and The Barbarians’, http://art.teleportacia.org/observation/vernacular (20-04-2006).

9. For a recent discussion of the open-source ideal see Boomen, M. van den, Schäfer, M. T. (2005) ‘Will the Revolution be Open-Sourced? How Open Source Travels Through Society’, How open is the Future? Economic, Social and Cultural Scenarios inspired by Free and Open Source Software, Wynants, M., Cornelis, J. (eds.), Brussels. (also at http://crosstalks.vub.ac.be/publications/howopenisthefuture/crosstalks_book1.pdf 20-04-2006)

10. For a discussion of the spatial turn in cultural studies see Massey, D. (2005), For Space, London, SAGE; Couldry, N., McCarthy, A. (eds.) (2004), Mediaspace. Place, Scale and Culture in a Media Age, London: Routledge.

11. Foucault, M., Miskowiec, J. (1986), ‘Of Others Spaces’, Diacritics, 16: 1 , pp. 22-27 (also at http://foucault.info/documents/heteroTopia/foucault.heteroTopia.en.html 20-04-2006). Hayles, N. K. (2002), ‘Flesh and Metal: Reconfiguring the Mindbody in Virtual Environments’, Configurations, 10: 2, pp. 297-320, Poster, M. (2004), ‘Digitally Local Communications: Technologies and Space’, conference paper, The Global and the Local in Mobile Communication: Places, Images, People, Connections, Budapest. (http://www.locative.net/tcmreader/index.php?cspaces;poster 20-04-2006).

12. Legrady, G. (1999), ‘Intersecting the Virtual and the Real: Space in Interactive Media Installations’, Wide Angle 21/1: 104-113, here p. 105, reprinted in Rieser, M., Zapp, A., (eds.) (2005), New Screen Media. Cinema/Art/Narrative, London, pp. 221-226.

13. Legrady (1999), p. 106.

14. Harrison, S., Dourish, P. (2001), ‘Re-Place-ing Space. The Role of Space and Place in Collaborative Systems’, Computer Supported Cooperative Work, Proceedings of the 1996 ACM conference on Computer supported cooperative work, Boston, Massachusetts, United States, pp. 67-76, here p. 73. See also Dourish, P., Where the Action is. The Foundation of Embodied Interaction, Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

15. For the development of tool metaphors and early paint programs, see Smith, A.R. (2001), ‘Digital Paint Systems: An Anecdotal and Historical Overview’, IEEE Annals of the History of Computing, 23: 2, pp. 4-30.

16. McCullough, M. (1996), Abstracting Craft. The Practised Digital Hand, Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

17. Bolter, D., Grusin, R. (1999), Remediation. Understanding New Media, Cambridge Mass.: MIT Press.

18. Ryoaki, K., Marti, S., Ishii, H. (2004), ‘I/O Brush: Drawing with Everyday Objects as Ink’, Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on Human factors in computing systems, Vienna, Austria, pp. 303- 310 and http://web.media.mit.edu/~kimiko/iobrush/ (20-04-2006)

19. http://smoothware.com/danny/neweasel.html (20-04-2006)

20. The term ‘showing making’ is based on William Mitchell’s ‘showing seeing’, which he uses to illustrate the way visual culture should be addressed in education and research, Mitchell, W.J.T. (2002) ‘Showing seeing: a Critique of Visual Culture’, Journal of Visual Culture: 1, pp. 165-181.

21. A lot has been written on the impact of computer generated imagery on the perception of reality, and the fascination as well as anxieties caused by it. See for example Mitchell, W.J. (1992), The Reconfigured Eye. Visual Truth in the Post-photographic Era, Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press; Savedoff, B. (1997), ‘Escaping Reality: Digital Imagery and the Resources of Photography‘, Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 55:2, pp. 202-214; Manovich, L. (2001), The Language of New Media, Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press. On computer graphics hunt for photo-realism see Jones, B. (1989), ‘Computer Imagery: Imitation and Representation of Realities’, Leonardo: Journal of the International Society for the Arts, Sciences and Technology, Computer Art in Context Supplemental Issue, pp. 31-38, Moskovich, J. (2002), ‘To Infinity and Beyond: Assessing the Technological Imperative in Computer Animation’, Screen, 43:3, pp. 293-314.

22. The ‘making-of’ has not yet been central subject to academic study. In a brief analysis within his book on the trailer, Vincent Hediger turns to psychoanalytical theory to explain the fascination with showing processes of making. Citing the work of Kaja Silverman and Slavoj Žižek, Hediger states that showing the machinery behind the illusion will enhance the viewers desire for illusion. Hediger,V. (2001), Verführung zum Film. Der Amerikanische Kinotrailer seit 1912, Marburg, p. 136.

23. Fuller, M., ‘Data Nudism’, An Interview with 0100101110101101.org about life_sharing, www.walkerart.org/gallery9/lifesharing/; Baumgärtel, T., ‘Portrait of the Artist as a Hard Disk’, Eyestorm and ibid., ‘The Self on the Screen’, Selfware http://www.eyestorm.com/feature/ED2n_article.asp?article_id=300&caller=1, all three also at http://www.0100101110101101.org/home/life_sharing/media.html (20-40-2006).